The yellow fever epidemic in the fall of 1862 was one of the greatest

natural disasters in Wilmington’s history

By Dr. Chris Fonvielle

People rushed to the riverfront to watch a splendid steamship slowly make her way up the Cape Fear River. They clapped and cheered as she tied in at the foot of Dock Street while sailors on board whooped and waved their caps in celebration of their successful run through the U.S. Navy’s blockade of Wilmington, North Carolina.

The ship was the Kate, a Charleston, South Carolina-based blockade-runner smuggling supplies into the Confederacy. This was her first voyage to Wilmington, as she operated mostly in and out of her home port. It would be a fateful trip for a more grim reason. Within four months of the Kate’s arrival on August 6, 1862, yellow fever had claimed the lives of at least 7 percent of the town’s population and residents held her responsible.

Within days of the war’s first battle at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor in mid-April 1861, President Lincoln proclaimed a naval blockade of the seceded states. He knew that the South — a region of mostly farmers, planters and slaves but only 16 percent of the nation’s factories — would turn to European markets to procure both military supplies and civilian goods when war came.

Critics disregarded the blockade as a violation of international law, which defined a blockade as an act of war between belligerents. President Lincoln, however, refused to acknowledge the sovereignty of the newly established Confederate States of America. European governments vowed to remain neutral during the American conflict, but the potential for huge profits in trading guns for Southern cotton lured speculators on both sides of the Atlantic into the smuggling trade. Businessmen in the South and Europe, especially Great Britain, which became the Confederacy’s biggest trading partner, established importing and exporting companies and developed strong trade alliances. John Fraser & Company of Charleston, which owned the Kate, was one of the more prominent firms. The Confederate government and state governments, including North Carolina, also invested heavily in blockade running.

The U.S. Navy faced an impossible task trying to stop the illegal trade. Too few ships at the beginning of the war and a lack of political and logistical support hampered its efforts. Moreover, the South’s 3,549-mile-long coastline — extending from the Virginia Capes to the Florida Keys and then around to the Texas-Mexico border — compelled Union blockading vessels to concentrate their efforts against the South’s major seaports, including New Orleans, Charleston, Savannah and Wilmington, among others.

Wilmington became the most popular point of entry for blockade-running ships. It was close to British trans-shipment points at Bermuda and in the Bahamas, where oceangoing merchantmen carried supplies destined for the Confederacy. There the cargoes were transferred to smaller, swift blockade-runners for the final dash into Southern seaports.

Blockade-runners enjoyed a success rate of about 80 percent at Wilmington, as the Cape Fear River could be accessed by one of two entryways — Old Inlet, the main bar and New Inlet, a shallow strait 6 miles to the northeast. Bald Head Island and Frying Pan Shoals separated the inlets, offering blockade-runners a choice of entry and exit at the harbor. Unable to adequately cover both inlets, Union blockaders faced utter frustration. “(Blockading Wilmington) was very like a parcel of cats watching a big rat hole,” observed one naval officer, “the rat often running in when they are expecting him to run out and visa versa.”

After Union military forces captured Norfolk, Virginia, as well as North Carolina’s Outer Banks and port towns along Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds in the spring of 1862, Wilmington became the closest major seaport to the Virginia battlefront. Three railroads linked Wilmington with key cities in the Carolinas and Virginia. The Wilmington and Weldon Railroad, which connected the Tar Heel port to Petersburg, Virginia, became the “Lifeline of the Confederacy” for supplying General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

The Union blockade was so weak during the first two years of the war that all types of ships, mostly sailing vessels, were employed as blockade-runners. Slowly but surely the number of Union blockaders increased through construction, purchase and the conversion of captured blockade-runners into cruisers. As the blockade tightened, more Southern seaports were either effectively blockaded or captured with the assistance of Union Army forces. As a result, the Confederacy turned to using speedy steamships to run the U.S. Navy’s gauntlet. The Kate was only the third steamship to run the blockade at Wilmington.

The Kate was built as the Carolina, a wooden-hulled side-wheel steamer, by Samuel Sneeden of Greenpoint, New York, in 1852. John Fraser & Company of Charleston purchased the ship in December 1861 to use as a blockade-runner. George Alfred Trenholm, the company’s chief executive officer, renamed her Kate for his son William’s wife, Kate MacBeth Trenholm.

The Kate became one of the most successful Confederate commerce vessels, reportedly making 20 runs through the Union blockade between January and November of 1862. Trenholm considered the Kate the workhorse of his flotilla of blockade-runners, and the profits she earned enabled him to purchase additional ships.

Trenholm assigned Thomas J. Lockwood of Charleston to captain the Kate, which he nicknamed The Packet because of her impressive speed and success. Lockwood or Trenholm allegedly was the inspiration for Margaret Mitchell’s fictional character Rhett Butler in her 1936 book, Gone With the Wind. Either way, blockade-runners became an important part of American popular culture in the late 1930s. C.C. “Kit” Morse of Smithville (modern Southport, North Carolina) served as the Kate’s pilot, guiding her in and out of Charleston and Wilmington without ever getting caught by Union blockaders.

Perhaps Kit Morse’s connection to the Cape Fear prompted Trenholm in part to send the Kate to Wilmington. She sailed on Aug. 2 from Nassau in the Bahamas, where a yellow fever outbreak was underway. By the time the Kate reached Wilmington four days later, at least one crewman was fevered. Other sailors reportedly soon fell ill. After discharging her shipment of bacon and other food supplies and loading up with cotton for her outward voyage, the Kate made a quick turnaround and sailed from the Tar Heel seaport.

Rumors of yellow fever in Wilmington began soon after the Kate’s departure, although several residents had died of the disease earlier that summer of 1862. Agues, a catch-all term for fevers in those days, were a common occurrence during the hot months, which people referred to as the “sickly season.” When temperatures got hot, people got sick, especially in urban centers.

Decades before doctors possessed any knowledge of germs, bacteria and viruses, they believed in the airborne theory for the spread of diseases. Rotting refuse and carcasses of dead animals, stagnant ponds and swamps all created miasmic, noxious and pernicious vapors responsible for illnesses and death. Low-lying areas and cellars overflowed from frequent heavy rains in June, July and August in Wilmington.

Local newspapers reported on the swarms of annoying mosquitoes, but doctors never connected the Aedes aegypti to the spread of the yellow fever virus. Even so, residents facetiously remarked that the disease was likely the plot of a Yankee mosquito. “A new mosquito has been invented recently in these parts,” reported the Wilmington Daily Journal on Aug. 22, 1862. “This mosquito, while screwing in his bill, sings ‘Yankee Doodle’ and other anti-Confederate airs through his hind legs.”

Father Thomas Murphy of St. Thomas Catholic Church on Dock Street performed the funeral of Henry Smith, a 30-year-old Irishman who died of yellow fever exactly one week after the Kate’s arrival. James Sprunt, an early chronicler of Cape Fear history and a postwar cotton magnate, claimed that Lewis Swarzman, a 36-year-old, German-born wood and coal dealer who provided fuel for the Kate’s outgoing voyage, was the first official victim of the yellow fever epidemic, although Swarzman’s obituary reported that he died of a stroke. Whatever caused his death, rumors began spreading as fast as the fever.

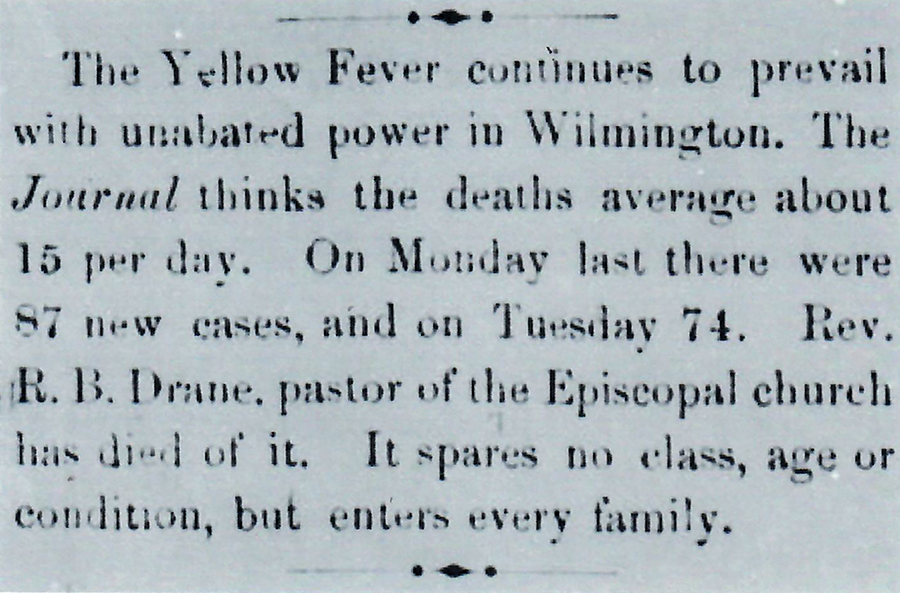

Doctors announced in mid-September that they had documented only five yellow fever cases. By the end of the month, however, the numbers had increased dramatically, and new patients overwhelmed Wilmington physicians Thomas B. Carr, James Dickson, James F. McRee and others. Hoping to prevent a public panic, Mayor John Dawson ordered that the ensuing crisis be investigated, but the number of cases grew day after day after day. By the end of September, doctors conceded that Wilmington was in the throes of a full-blown yellow fever epidemic.

The disease began innocuously enough with a fever, chills and diarrhea, but eventually gave way to internal hemorrhaging, black vomit and jaundice. It did not discriminate as to its victims. Mary Ashe McRee, the wife of Dr. James F. McRee, died of yellow fever. Griffith J. McRee, a prominent citizen, lost his mother, wife, young daughter, and teenaged son and namesake. It also claimed the life of Georgia Weeks, who worked in a house of ill-repute called the Hole in the Wall. James Quigley, the superintendent of Oakdale Cemetery, succumbed on Oct. 15, 1862, his 32nd birthday.

A number of local doctors, ministers and nurses risked their lives to care for and comfort the sick, and in some cases fell victim to the disease themselves. Rector Robert B. Drane of St. James Episcopal Church, Reverend John L. Pritchard of First Baptist Church, and Dr. James Dickson all died of mosquito bites while tending to patients of the so-called “yellow jack.”

To combat the perceived airborne disease, residents began burning barrels of turpentine and rosin in their yards and on street corners which, ironically, kept mosquitoes at bay. The smoldering fires also created a pall of thick black smoke that hung over the town. Acting on doctors’ recommendations, civil authorities instructed residents to pump out excess water from their cellars, clear garbage from their properties, and remain indoors after darkness.

As casualties mounted in late September, panicked citizens who could afford to leave town packed their belongings and fled to Wrightsville Sound or Masonboro Sound. Others sought refuge in towns in the Piedmont and the mountains of North Carolina. Although they did not understand why, ocean breezes and cooler temperatures inland created healthier environments. Armand John DeRosset’s family escaped to Chapel Hill. Yet some communities, including Fayetteville and Lumberton, either quarantined refugees from Wilmington or denied them entry altogether.

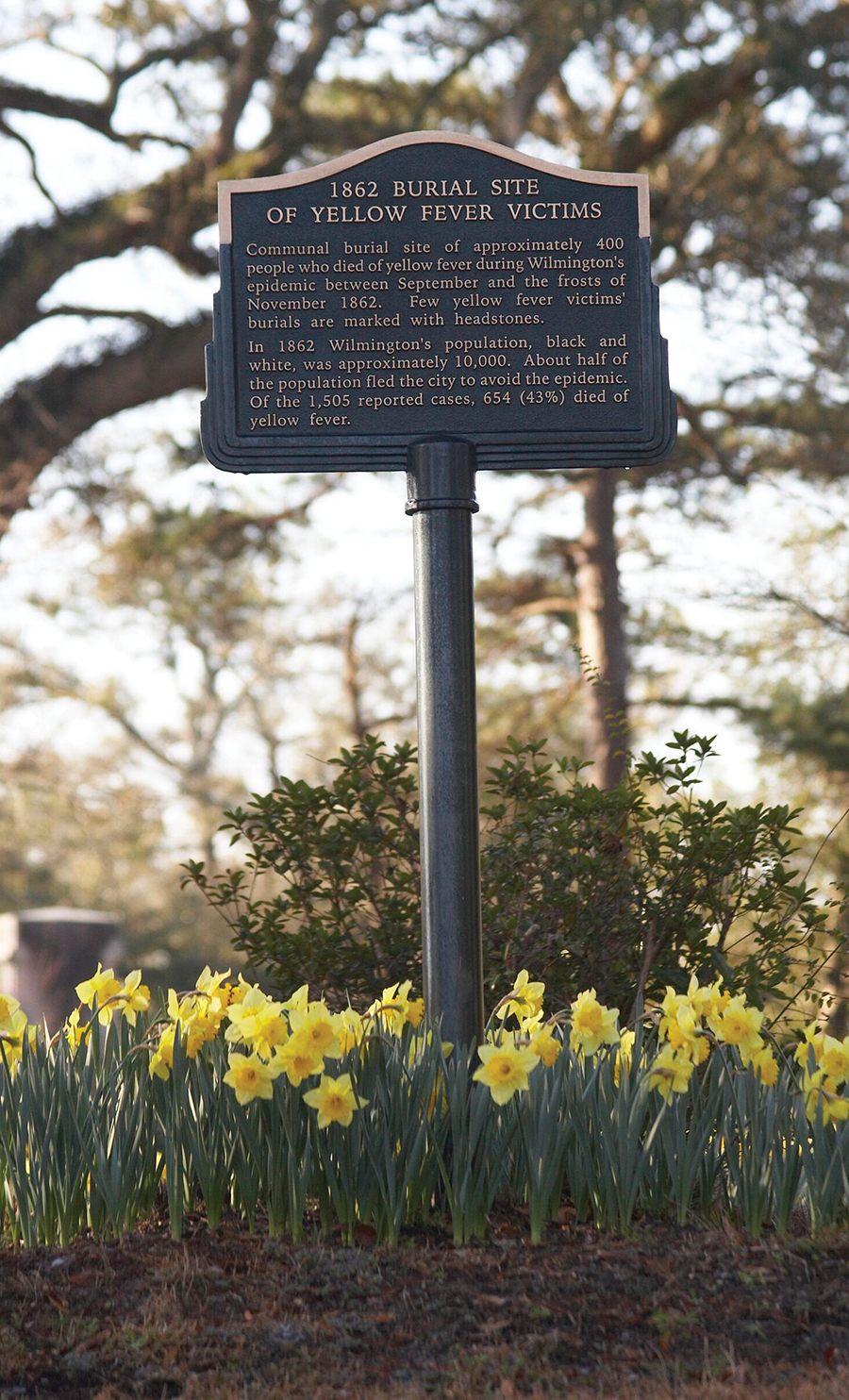

James Fulton, editor and publisher of the Wilmington Daily Journal, maintained a daily account of the disease’s progress, but eventually even he suspended operations and left town. The telegraph bureau also closed, and train and mail service ran irregularly. Wilmington became a virtual ghost town, as perhaps half the population of 10,000 people departed. The Confederate Army also vacated its troops, moving them downriver to Fort Fisher at New Inlet. “Silence reigned everywhere,” observed one eyewitness. “The dogs howled from hunger, and the very birds of the air had deserted the city. Death and pestilence had possession of every place. Want and misery was everywhere discernible.”

Residents who remained behind — disproportionately poor whites, free blacks and slaves — bore the brunt of the epidemic.

At its height in mid-October, as many as 15 people a day were dying. “Oct. 14th summed up for twenty-four hours previous, 87 new cases and 43 interments,” penned one diarist. “The report for Saturday, the 18th, gives the number of new cases for the same period at 500, and the number of interments for the same period at 150. This was the terrible week.”

Writing many years after the war, John D. Bellamy Jr. vividly recalled watching corpse-bearing wagons roll past his family’s grand home at Market Street and Fifth Avenue, heading toward Oakdale Cemetery in the eastern suburbs. Unable to receive proper burials, more than 400 victims were interred in hastily dug graves on an otherwise pleasant grassy slope in Oakdale’s public grounds still known as Yellow Fever Hill.

Wilmington’s abandonment by many white residents proved beneficial for some enslaved African-Americans. Fewer whites meant less security, as serving in slave patrols to prevent escapes and revolts was mandatory for white men. William Benjamin Gould, an enslaved plasterer who helped build the Bellamy Mansion, and seven fellow bonded men made their getaway on the night of Sept. 21, 1862. Launching a boat at the foot of Orange Street, they rowed 28 miles down the Cape Fear River to freedom. Early the following morning, the blockading ship USS Cambridge picked them up at Old Inlet. Other slaves, although their numbers are unknown, also participated in the “great escape” as yellow fever raged in Wilmington.

At the urgent request of Mayor Dawson, who remained in Wilmington, Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard at Charleston sent his personal physician, Dr. W.T. Wragg, to the Tar Heel seaport. Until his arrival, people tried all kinds of experimental treatments to combat the disease, including putting a cloth patch soaked in “gas tar” on the chest of a fevered person. Experienced in treating both yellow fever and malaria, Dr. Wragg administered regular doses of quinine to his patients, with modest success. Nuns from Charleston’s Convent of Our Lady of Mercy also came to Wilmington to serve as nurses, some of whom fell prey to the fever and were buried at the Catholic cemetery on the Topsail Sound Road (formerly located near the St. Mary’s development at Market and 23rd Streets).

When General W.H.C. Whiting arrived in mid-November to assume command of the District of the Cape Fear, he found Wilmington undefended and in disorder. He feared the Union Army might take advantage of the chaos by launching an overland assault from their base at New Bern only 90 miles to the north, or by a landing an expeditionary force at Wrightsville Beach for an advance against Wilmington from the east. Whiting need not have worried, as Union military personnel feared yellow fever, which they knew gripped Wilmington, more than battling Confederate soldiers. The anticipated attack never materialized.

Along with Gen. Whiting, November brought cooler weather, which abated the yellow fever and killed the hordes of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Traumatized residents slowly returned home, but wondered if their town would ever truly recover.

According to statistics compiled by James Fulton of the Wilmington Daily Journal, yellow fever killed at least 654 people of 1,500 reported cases. The numbers were likely higher as African-American casualties went underreported or unreported. Whatever the exact figures, the 1862 yellow fever epidemic was one of the deadliest natural disasters in Wilmington’s history. Convinced that the Kate was to blame for all the hardship and death, Wilmingtonians came to view blockade-running as a necessary evil at best.

James Sprunt put it well when he wrote that “blockade-running was both life-preserving and death-dealing for the Confederacy.” That was certainly true for Wilmington. b

Dr. Chris Fonvielle is professor emeritus in the Department of History at UNC Wilmington, and the author of articles and books on the Civil War in North Carolina and the history of the Lower Cape Fear. Upon his retirement in 2018, he was awarded the Order of the Long Leaf Pine in recognition of his distinguished service to the state of North Carolina.