The enduring legacy of Hugh MacRae Morton

By Susan Taylor Block

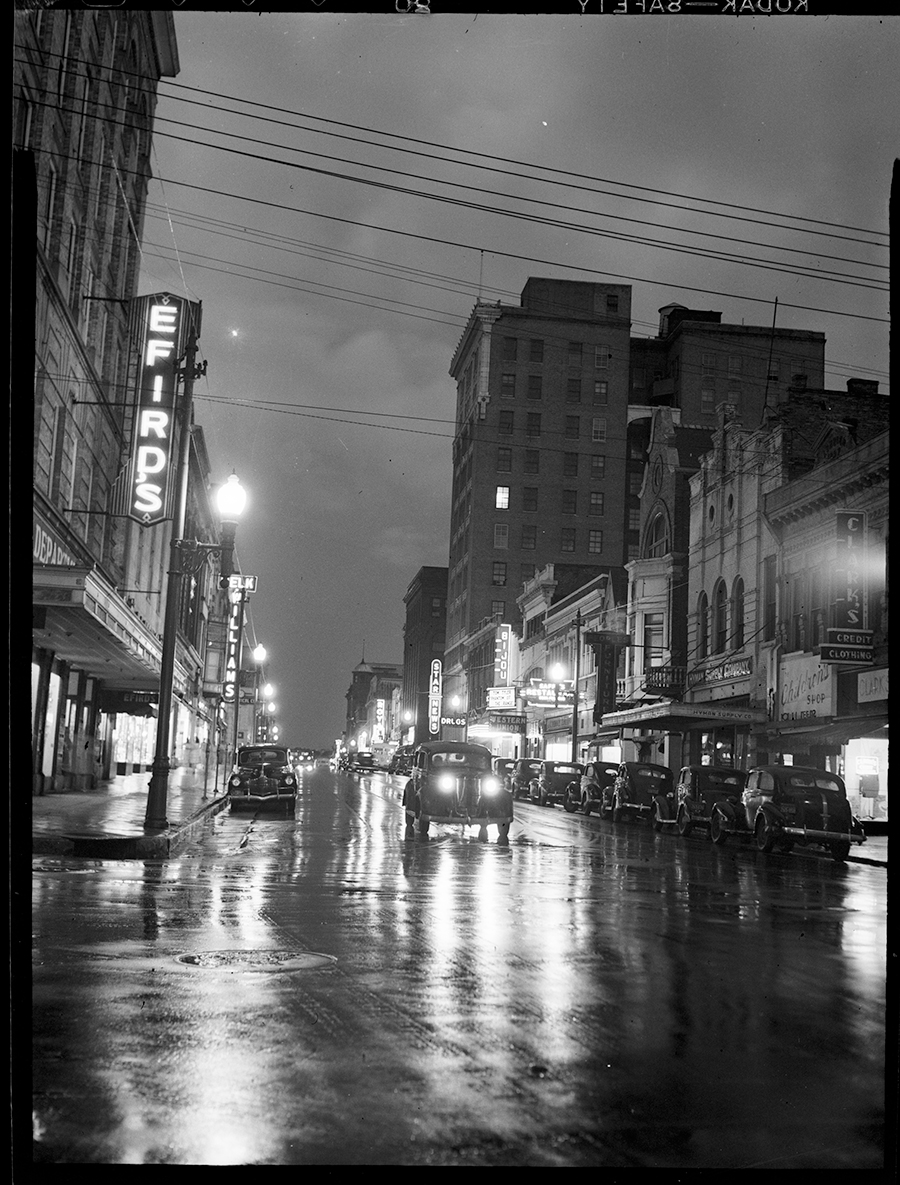

Photographs by Hugh Morton, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina Library at Chapel Hill

Ihave always loved staring at photos, particularly those with some age. One day, when I was a little girl, my mother told me I could not go in the “picture drawer” of her desk anymore because I was wearing out the old images. Forbidding access only enhanced my interest in image gazing. I have the desk now, and I still smile sometimes when I pull out that drawer. Photographs are the is-ness of the was. Wilmington native Hugh Morton (1921–2006) knew that in the deepest way.

Much has been written about the accomplishments of Hugh Morton of Wilmington and Grandfather Mountain. Rather than serve as an echo, I want to share my own fond memories of working with him on a number of writing projects. Each was enhanced by his photographic skills and exquisite sensitivity to photo-worthiness. Growing up in Wilmington, I knew the name Hugh Morton, but I never remember having seen him until about 1969. A friend pointed him out in the press pool at a Carolina basketball game in Carmichael Auditorium. My first impressions were of concentration and calm. My last impressions of him were the same.

Much later, in 1995, I wrote a short book titled Van Eeden. That was the name of a farm settlement owned by Hugh MacRae, grandfather of Hugh Morton. Van Eeden was first settled by immigrants from Holland. While doing research on Van Eeden in the North Carolina Collection at UNC, I happened upon the fact that Jews settled on farms in Van Eeden in the late 1930s. Jews farm? I never had heard of that in southeastern North Carolina. As it turned out, the last group of immigrants did farm a bit, but mostly because agricultural visas were the last tickets out of Hitler’s regime. About a dozen Jewish families who almost certainly would have been tortured and murdered escaped to Van Eeden, where they learned the rudiments of agriculture while longing for a more lucrative future in big Northern cities.

Not long before Van Eeden went to print, I called Mr. Morton to ask if he had a photograph of his grandfather that might match well with such a subject. He did, and that picture, taken roughly 50 years before Van Eeden was published, became a wordless introduction to the booklet. Mr. Morton called me back later to offer a few memories the photo had stirred to the top of his mind, as if the photograph were a spoon; and the past, a bowl of pudding.

The picture arrived in my mailbox within a few days of my request. It was in perfect condition, and was sealed in a big white envelope with a “Grandfather Mountain” return address. From that time on, my heart must have beat a bit faster when I spotted any big white envelope in the day’s mail. I always was hoping for another “Morton,” and another explanatory phone call.

It was interesting to hear him talk. His voice was strong but soft, like rock wrapped in velvet. Both the sound of his voice and the cadence of his words were similar to the sound and rhythm in which his relatives speak today. Hugh MacRae II, Hugh MacRae III, and Daniel MacRae; all speak in like fashion. On the female side, Mr. Morton’s daughter, Catherine, also has speech patterns that remind me of her father.

In 1997, Janet Seapker, director of the Cape Fear Museum, asked me to write a trilogy of photograph anthologies that I titled Along the Cape Fear, Cape Fear Lost and Cape Fear Beaches. It was then that Mr. Morton began to send photos much more frequently, and that trend held for almost 10 years. Since the first book was to be a miscellany, I wrote and asked if he would share local photos with me that had some poetry embedded in them. A few days later, he called me from Orton Plantation, where he was visiting his lifelong friend, Kenneth Murchison Sprunt. “Po-e-try?” Mr. Morton asked, slowly.

That request yielded a large number of prints, and there was, indeed, a bit of poetry in each.

At some point, Mr. Morton asked me to meet him one day for lunch, to go over the next request for photos. I was looking forward to a delicious light meal and wondered what sort of car he drove. The restaurant he chose was a popular local eatery that featured heavy sauces and porterhouse steak; and he pulled up driving a broken-in Oldsmobile. Another thing that illustrates the refreshing down-to-earth-ness of this mountain dweller was the fact that while developing Wilmington’s South Live Oak Parkway in Wilmington, he himself planted the trees.

Working with Hugh Morton to use his photographs as illustrations, explanations and celebrations was a grand experience, but what I remember most was a comment he had made in the “local eatery.” He referred to the afterlife, and said that there would be rewards for hard work. It seemed to me that Mr. Morton worked all the time. Even snapping pictures of Michael Jordan suspended in air was work for him because he always sought perfection. I am but one of hundreds of writers who benefited from the work and inspiration of Mr. Morton. I will always be grateful.

There came a time when mailings from Mr. Morton became less frequent. Then one day he called from Grandfather Mountain to tell the sad news that he was sick. His doctor said that he would not be “around” for very long. I will always miss having a friend like him who fully understood getting gloriously engaged in a two-dimensional world. But there will always be his pictures.

Hugh Morton’s photograph collection is carefully stored and preserved in Wilson Library, at the photographer’s beloved alma mater, the University of North Carolina. Robert Anthony Jr. is curator of the vast North Carolina Collection, in which the Morton photos are housed. Stephen J. Fletcher, the North Carolina Collection photographic archivist, states that the total number of Hugh Morton photographs housed there is “about 250,000.”

Susan Taylor Block is one of Salt’s earliest contributors.

Hugh Morton (1921–2006),

Conservationist and Photographer,

At a Glance:

1935: Time magazine published one of Hugh Morton’s photographs for the first time when he was only 14 years old.

1942–45: Hugh Morton was awarded both the Bronze Star and Purple Heart, after being wounded in the line of duty as a newsreel photographer.

1948: Morton served as the first president of the Azalea Festival. He caused the event to be a great success because of his promotions, careful choosing of celebrities and leadership skills, launching the largest and longest running locally run celebration in North Carolina history.

1950: Hugh Morton gave Andy Griffith an assist when he invited him to do a standup comedy routine for the North Carolina Press Association. That event launched Griffith’s career.

1952–2006: Hugh Morton inherited Grandfather Mountain and added the Mile High Swinging Bridge, Visitors Center, a Weather Reporting Station, nature museum, theater and wildlife habitats for native species. Rather than allow the National Park Service to bore through Grandfather Mountain to create a 7.7-mile stretch of the Blue Ridge Parkway, Morton directed the government to build Linn Cove Viaduct, a solution that preserved the ancient beauty and order of the mountain. Hugh Morton contributed 3,000 acres of Grandfather Mountain to the Nature Conservatory.

1961: More than any other man, Hugh Morton made it possible for the USS North Carolina to be berthed permanently in the Cape Fear River. His connections, promotions and cheerleader spirit brought the ship to its new home. Everything went smoothly until the battleship collided with a floating seafood restaurant, and Hugh Morton even turned that into a positive publicity tool by sharing photos he took of the incident.

1982: A longtime sports photographer for UNC, Hugh Morton chose Michael Jordan to crown Lynda Goodfriend, Queen Azalea XXXV, just 10 days after freshman Jordan sunk the winning shot in the 1982 NCAA Tournament.

1990: President George H.W. Bush presented Morton with the Theodore Roosevelt Award for Conservation.

1995: He produced film documentaries including The Search for Clean Air on PBS, narrated by Walter Cronkite.

1988-2006: Morton received at least seven honorary doctorate degrees from Belmont Abbey, Lees-McRae College, Queens College, UNC Asheville, UNC Wilmington, Appalachian State and NC State.

2003–2006: He published two books, Hugh Morton’s North Carolina and Hugh Morton: North Carolina Photographer.

There is little documentation of Hugh Morton having exchanges with other Wilmington photographers, but Morton and Louis T. Moore did converse from time to time. Mr. Moore took a thousand panoramic shots of southeastern North Carolina. The two met periodically, from 1945 until 1961. “Mr. Moore was a great man,” wrote Morton, in 2000. “He, for the most part, had influence on me from the standpoint of appreciating history. I learned more from him about history, and the role that my family played in it.” Orton Plantation was a favorite subject for both of their cameras, and it seems they would be pleased to know that Mr. Moore’s grandson, Louis Moore Bacon, now owns Orton.