Where poets and nature meet

By Gwenyfar Rohler • Photographs By Andrew Sherman

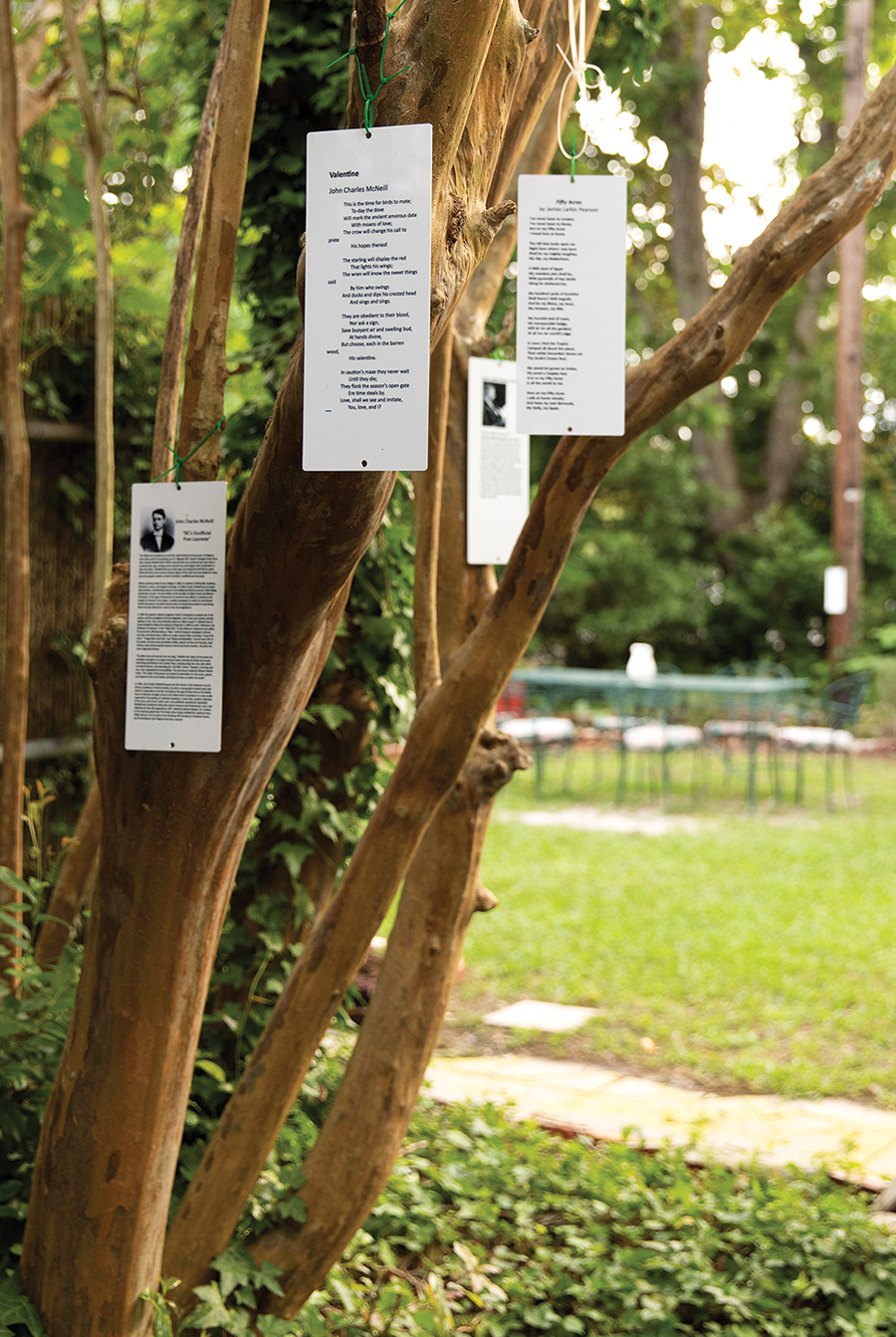

Some people have Christmas trees. I have “poet-trees.” Literally, poets and poetry hang from the trees in my garden . . . and the trellises, fences. I call it the North Carolina Poet Laureate’s Garden of Verse.

If I could tell you anything about my garden it is this: It is a fairy-tale place, for me at least, complete with the discovery of my playhouse, which was hidden beneath years of overgrown brambles, just like Sleeping Beauty’s castle, or Mary’s secret garden. Last year, I opened Between the Covers: A NC Writer’s Bed and Breakfast in my former childhood home. As the name implies, it celebrates North Carolina writers — and one subset of this group that captures my imagination and curiosity is the North Carolina poet laureates.

My house was built around the same time the poet laureate idea was born, the turn of the 20th century. In 1906 John Charles McNeill received the Patterson Cup (the first literary trophy for North Carolina), which was presented to him by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. From then on he was referred to as the poet laureate of North Carolina (it is even inscribed on his tombstone). In the intervening century, both the idea of the poet laureate, and my garden, have grown beyond expectations.

About six years ago, I had an idea that the poems would somehow be incorporated into the garden. But as far as creating this next phase of life for garden and maintaining it — that was something I needed help visualizing and making manifest. Enter Dagmar Cooley of Dagmar’s Designs and her amazing team.

This wasn’t going to be a project in which we ripped everything out and started from scratch. Preserving the hand-grafted camellias that date to just after World War II was important. Keeping the two pecan trees that the Hoopers (the family that built the house) gave each other as presents one year was essential. So was saving the heritage rose that climbs along the back fence. Yes, we have planted more climbing roses to continue the theme, but that’s the one my mother picked flowers from to weave into my hair for my soiree when I was little.

It is a space that is full of surprises. When we first moved into the house, a redbud tree had fallen and was supported by a concrete birdbath. It was tangled around a downed electrical line. The combined health and safety hazards necessitated its swift removal. Last week Cooley showed me the redbud tree that has started growing, over 30 years later, in the same spot. Incorporating the history of the property and the history of literature in our state with a plan to move forward wasn’t going to be simple.

“I think you’re almost there, Gwenyfar,” Cooley mused. “What you really lack is structure.” She explained how the garden was really composed of different “rooms.” The backyard, particularly, has an unusual shape; it wraps around the side of the house and then takes a weird S-curve around the other side, accommodating a corner lot that was cut out of the property and sold decades ago to create my neighbors’ house. The penny dropped: Just like a poem that has a beautiful idea but lacks structure to communicate its main theme, the garden was filled with great ideas but was sort of all over the place.

“When embarking on a journey, it’s important to have people that you travel well with and that share a common goal and/or excitement about the excursion,” Cooley added. Many of her clients are focused on trying to make their spaces achieve a specific look in the space of one season. So working on this project is a little different. For example, when we began discussing asparagus — which I have tried (and failed) to grow repeatedly — she pointed out that you couldn’t harvest it for the first two years.

“I’m going to own this house for almost 100 years; what’s a two-year wait?” I shrugged.

Cooley smiled, nodded and arrived the following week with several different varieties of asparagus crowns to plant, including Martha Washington, Purple Passion and Jersey Supreme. That has been a refrain over and over. I waited six years to eat a fig from the fig tree and five to eat blueberries from the garden. Both of those juicy rewards Cooley made possible in the face of some pretty crazy obstacles that include drought, squirrels, birds and hurricanes. In the midst of my quest for an edible and ornamental garden, she has transformed the untamed jungle of memories and ideas into a thing of beauty.

“I have clients that have blueberries, but they aren’t sweet at all,” Cooley noted between mouthfuls of berries. “I think it’s something else that happens here.” She smiled. “Part of it is probably the ashes from your fireplace, but I think a lot of it is how much lovin’ they get.”

Not Just a Simple Group

When I hit on the idea of a Poet Laureate’s Garden, it created a variety of logistical issues. The first was how to actually display the poetry and the poets’ biographies. I planned to represent each of the laureates with a short biographical sketch and at least two different pieces of poetry on display in the garden. One can overcomplicate things if given enough rope, and I came up with a dozen great but very expensive and difficult ideas before it finally hit me: We had a sublimation printer and a heat press at my bookstore. We use the setup for making coffee mugs, jigsaw puzzles, T-shirts, bandannas and other assorted literary accessories, including … signs! Would it be possible to make signs that would withstand the elements? After a couple of drafts were scrapped we came up with a 5-by-12-inch metal sign that we could put poems and bios on and hang in the garden.

But the North Carolina poet laureates are not a simple group of people to collect in one place. As mentioned, John Charles McNeill was the state’s unofficial poet laureate. The post was officially created in 1935, when the North Carolina General Assembly passed a resolution allowing the governor “to name and appoint some outstanding and distinguished man of letters as poet-laureate for North Carolina.” But it took until 1948 for Governor Cherry to get around to appointing Arthur Talmadge Abernathy to be the first official poet laureate.

Abernathy is a bit difficult: He didn’t actually publish a poetry collection, although his work appeared widely in newspapers and magazines during his lifetime. His successor, James Larkin Pearson, was appointed poet laureate in 1953 and served until 1981. The largely self-taught Wilks County native wrote poetry that utilizes traditional rhyme scheme and structure. His themes tend to be nature, love and his home. The poem hanging from my crape myrtle tree, “Fifty Acres,” is a lovely example. Here are the first two verses:

I’ve never been to London,

I’ve never been to Rome;

But on my Fifty Acres

I travel here at home.

The hill that looks upon me

Right here where I was born

Shall be my mighty Jungfrau,

My Alp, my Matterhorn.

Sam Ragan, former editor of The Pilot newspaper in Southern Pines, succeeded Pearson and served until his death in 1996. It was actually Collected Poems of Sam Ragan that almost got me run over on Third Street. I was so absorbed that I walked out in traffic with my nose in the book. The poem that had endangered me, “A Poet Is Somebody Who Feels,” seemed the obvious choice to put in the garden. When I sit on the glider under the pecan tree, I can read it on the camellia I used to call “the peppermint bush” when I was young, due to the beautiful pink stripes on the white flowers.

With the appointment of Fred Chappell as poet laureate in 1997, the office ceased to be a lifetime post. “You have these in your garden,” Cooley noted, tracing her finger down the poem “Narcissus and Echo.”

“Do you see the other poem contained within it?’ I asked, showing her the italicized poem contained within the larger piece. The first part of each line of the poem is in one typeface and the second part is italicized. You can read straight down the column of type on the left, or down the column of italicized font or read all three together. “It’s really three poems when you read it. Or is it one?” I mused. What it is, quite simply, is brilliant.

Heralding a New Era

It is no surprise the Fred Chappell heralded a new era for the poet laureate. Not only is his work beautiful, but his very being is committed to making art and literature accessible to as many people as possible in any way possible. During his tenure the poet laureate’s position began to change to one of service. Now the poet laureate is North Carolina’s literary ambassador, working to promote and develop the arts and poetry throughout the state.

But perhaps the appointment of the first woman to the position of poet laureate by Governor Mike Easley in 2005 was the sign of real changes to come. It seemed appropriate to me to display Kathryn Stripling Beyer next to Jaki Shelton Green, the first poet laureate of color, in our state. Green was appointed in 2018 by Governor Roy Cooper.

Beyers’ poem “Diamonds” greets me most mornings when I sit on the back steps and have a coffee break with the dogs while the breakfast for the guests is in the oven. There is usually a 15-20 minute span when the table is set, but the guests are not awake yet. Then I get to visit with Jaki and Kathryn and contemplate the new day in the presence of their greatness.

In the most prominent place I could find in the yard, the spot that everyone will pass entering or leaving the house, I have displayed George Moses Horton.

Beneath his heart-rending poem “George Moses Horton, Myself,” a bleeding heart glory bower (Clerodendrum thomsonine) curls upward.

George Moses Horton died before the poet laureate mantle was conferred upon John Charles McNeill. Horton was born into slavery and spent much of his life in Chatham County, North Carolina. He would drive a wagon to Chapel Hill to sell produce from the plantation where he lived and began composing poems for the students at the university, who would purchase them. His love poems were especially popular, and one can imagine this enslaved Cyrano de Bergerac creating odes for the lovely young ladies the undergrads admired. This was in the late 1820s and early 1830s. At the time that he was selling his work as a poet, the North Carolina legislature passed a law forbidding slaves to learn to read or write. Horton had hoped to earn enough money from his work to buy his freedom. However, his emancipation came during the Civil War. Horton subsequently moved to Philadelphia, and his work changed drastically. It would have to: His life had been altered in the most profound of ways.

Horton is one of my literary heroes, and although the state of North Carolina was not prepared to properly honor him during his lifetime (in the last few decades he has posthumously received honors, including a dormitory named after him at UNC, and a state historical marker), I decided, it’s my garden, and I can include him if I wish. Frankly, I don’t know how I could not. His poem is one of my favorites:

George Moses Horton, Myself

I feel myself in need

Of the inspiring strains of ancient lore,

My heart to lift, my empty mind to feed,

And all the world explore.

I know that I am old

And never can recover what is past,

But for the future may some light unfold

And soar from ages blast.

I feel resolved to try,

My wish to prove, my calling to pursue,

Or mount up from the earth into the sky,

To show what Heaven can do.

My genius from a boy,

Has fluttered like a bird within my heart;

But could not thus confined her powers employ,

Impatient to depart.

She like a restless bird,

Would spread her wing, her power to be unfurl’d,

And let her songs be loudly heard,

And dart from world to world.cigarettes. That fun would be interrupted when “the garden came

Gwenyfar Rohler spends her days managing her family’s bookstore on Front Street.