The Atlantic Coast Line’s Champion Davis made the legendary trains run on time — and he painted them purple

By Kevin Maurer • Photographs from the Wilmington Railroad Museum

He was known as “Mr. Coast Line.”

A dandy who rolled into Wilmington most Saturdays on a train painted royal purple, he was impossible to miss strolling downtown dressed in a tailored suit, straw boater in the summer and a polished cane.

Champion McDowell Davis had high standards for both his clothes and his rail line. Under his leadership, the Atlantic Coast Line’s main rail line was double-tracked, signs and car numbers were painted with reflective paint, and he oversaw the switch from coal locomotives to diesel. During its heyday in the 1950s, the Atlantic Coast Line promised to take Florida-bound tourists from New York to Miami in 24 hours.

But when standards weren’t met, Davis was known to use an extensive vocabulary of profanity. “He uses more polite (sic) swear words in normal conversation than any fellow Episcopalian I know,” a colleague said at Davis’s 75th birthday party in 1954.

Davis gave the rail line 60 years of his life — 15 of those as president. He had no wife. No family. Just work. “He worked for the same company for longer than some people lived,” says Mark Koenig, director of the Wilmington Railroad Museum. “He was a sober character when he approached his business.”

But in the end, on a Thursday in 1955, the railroad broke Davis’ heart when the Atlantic Coast Line’s board of directors decided to relocate the company’s headquarters to Jacksonville, Florida, after 115 years in Wilmington.

The World’s Longest Line

Although Wilmington is now known as the Port City, when the Wilmington to Weldon line was completed in 1840, the city became a railroad town.

Amazingly, the 161.5-mile line was at that time the longest railroad in the world, stretching from Wilmington to Weldon, a small town just south of the Virginia line near Roanoke Rapids. The city of Goldsboro — the midpoint of the Wilmington to Weldon line — owes its existence to the railroad, and by extension, to Champion Davis.

Champ Davis was born near Hickory in McDowell County, North Carolina, in 1879. His father moved to Wilmington to work for the railroad. Davis joined his father at the railroad on March 1, 1893, at the age of 13. He started as a messenger boy at the Wilmington & Weldon’s freight office before working his way up the ranks, first as a stenographer, then in 1898 as a rate clerk and two years later the chief clerk.

The Wilmington & Weldon merged with the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad in 1900. At that time, Davis was well on his way up the ranks. By 1911, he was a freight agent in Savannah, Georgia. He returned to Wilmington in 1920 as the rail line’s assistant freight traffic manager and five years later took over as freight traffic manager. By 1939, Davis was general vice president of the railroad.

When the Atlantic Coast Line’s president died suddenly in 1942, the board promoted Davis to president.

Royal Purple

One of Davis’ first acts was declaring purple the line’s official color. The engines and cars were all repainted. The color was unmistakable as the cars rumbled down the lines. He also increased the speed limit for trains heading between New York and Miami to 90 miles an hour.

The Atlantic Coast Line’s premier passenger train — The Champion — was named after its president.

“The Champ was always packed, and we didn’t stop serving dinner until everyone got fed . . . no matter how long it took,” James Longmire, who worked on the train, told an interviewer in 1992. “We called the Champ ‘Big Bertha’ because tips were so good we didn’t have to cash our paychecks.”

Under Davis’ leadership, the railroad was “generally regarded as one of the best maintained plants in the country,” according to Davis’ obituary in The New York Times. The paper notes that Davis was criticized by Wall Street for spending more on maintenance than the average railroad. Davis’ reply, according to the Times, fit with his reputation for high standards: “I do not recall that anyone has suggested that Coast Line retard its traffic and revenue growth so as to conform to an ‘average.’”

By 1955, more than 1,500 Wilmington residents were on the Atlantic Coast Line’s $6.5 million payroll, according to historical records. People joked that if you lived in the Port City, you either worked for Davis or knew someone who did.

But Davis always saw Wilmington as home. He had a house on 5th Avenue and had family land in Porters Neck, but his real home was on the rails. He spent most days in his office car traveling up and down the line, meeting with managers and inspecting the line’s stations and depots.

“He spends a large portion of his life in his office car, which no happily married man would be permitted to do, going over the entire Coast Line System, and thereby has a very unusual knowledge of the property, its needs, and above all, is acquainted with its various officers, together with many of its workers, who pull together as a team to make the Coast Line what it is,” said an executive, who represented the rail line’s board at Davis’ 75th birthday party in New York.

On Saturdays, Davis would arrive in Wilmington in time for a Sunday staff meeting with his executives before spending the rest of the day with his mother and sisters. But his work came at the expense of a wife and home life, a fact Davis reflected on during his 75th birthday celebration. “I did not overlook courtship, but the best I ever accomplished was to come out second best several times,” Davis said. “True, some of the objects of my interest later became widows and married again, but I was never in the race except on first try.”

The railroad was his wife, but that relationship ended in divorce.

Black Thursday

A year after Davis’ 75th birthday celebration, the board announced plans to move the railroad’s headquarters from Wilmington to Jacksonville, Florida, on December 10, 1955, a date that became known as Black Thursday in Wilmington history.

But the reason for the move seemed to be more about geography and politics than anything else. The Atlantic Coast Line’s completion of the Fayetteville Cutoff train line from Wilson to Florence, South Carolina, trimmed 60 miles off the north-south route and made the line to Wilmington a dead end. The Atlantic Coast Line was also looking to add the Florida East Coast Railway to its network. Bringing jobs to Florida would help the Atlantic Coast Line’s case with state regulators scrutinizing the deal.

Julie Rehder, marketing and public relations administrator at Davis Health Care, which was founded by Champ Davis and opened in 1966, told the StarNews that Davis and the board were at odds: “By that time, he had done all he could for the Atlantic Coast Line and had lost some favor with some other railroaders who no longer appreciated his style, the very style that had made the Atlantic Coast Line so successful,” Rehder said. “Champ wanted it to be the best railroad in the country and by 1951 he said, ‘There is no better track structure, roadway, and riding track in the United States than that of the Coast Line, particularly the Richmond-Jacksonville line.’”

Koenig said Davis postponed the line’s move for years but couldn’t stop it. But Davis’ legacy was painted on every car. “When the railroad left, they left with a couple of carloads of purple paint,” he said.

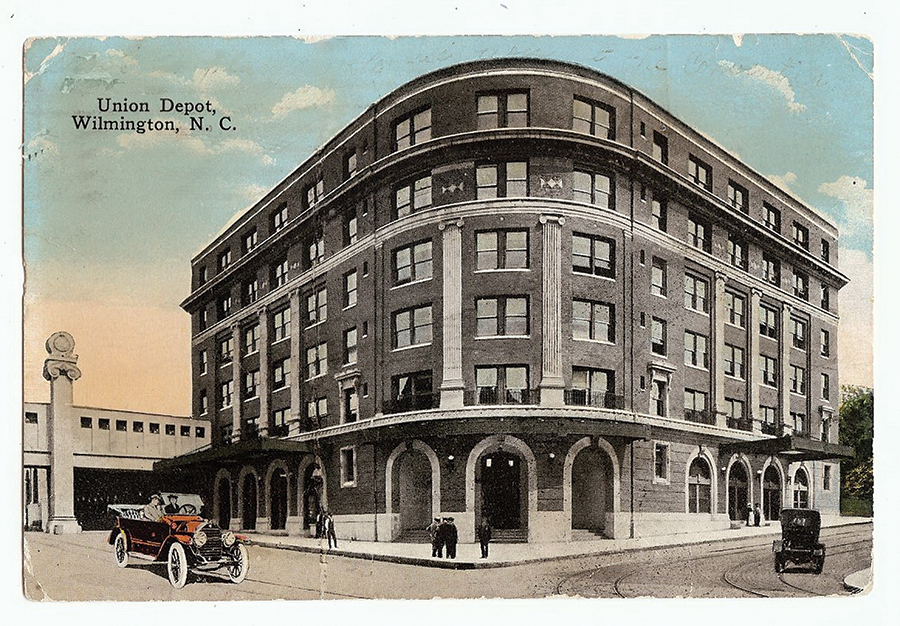

By 1960, the railroad was gone, leaving the city with four abandoned downtown buildings. One would become the Wilmington Railroad Museum. Another became the Coastline Convention Center. But nothing filled the void left by the Atlantic Coast Line. Even today, there is no passenger train service in Wilmington. A bus takes travelers to the Amtrak station in Fayetteville.

When the railroad left, so did Davis. He retired from the Atlantic Coast Line two years after Black Thursday. He sold all his shares in the company and refused a seat on the board. It was a clean break.

But Davis couldn’t stay idle for long. In 1963 he opened the Cornelia Nixon Davis Nursing Home. The 200-person retirement home was built near his family property at Porters Neck and named after his mother. “He’d greet folks at the retirement home on Sundays,” Koenig said. Now known as the Davis Community, the 50-acre facility for seniors features an assisted living center and a Rehabilitation and Wellness Pavilion for those recovering from knee and hip replacements.

Davis died in January 1975. He was 95. The retirement home is as much a part of his legacy as the railroad, if not more so. His ashes were spread at the nursing home, not on the railroad tracks.

Kevin Maurer is an award-winning journalist and author who lives in Wilmington. His latest book is American Radical: Inside the World of an Undercover Muslim FBI Agent.