And underwater wonders discovered on a day at the aquarium

By Virginia Holman

When I read that the Weeki Wachee mermaids were coming to the aquarium at Fort Fisher, my heart leaped like a child’s. I can’t tell you why, exactly, other than, squeal, MERMAIDS! Apparently, I was not alone. Within hours of posting on social media that the mermaids would appear for two weekends in March for special water shows and breakfasts-on-land, the events completely sold out, and families lined up at the doors an hour before the aquarium opened.

Mermaids aren’t part of the usual fare at our aquarium. The purpose of the aquarium is education and conservation, and though it hosts all manner of seasonal events for children, such as Trick or Treat Under the Sea, it is in no way a theme park, zoo or fun roadside attraction; it’s a place where people of all ages come to learn about our local marine life. But when Florida’s Weeki Wachee mermaids decided to take their show on the road to North Carolina to celebrate the 70th anniversary of both their show and the town of Kure Beach, it was hard to resist the appeal.

The first known mermaid story is of Atargatis, also known as Dea Syriae or the “Syrian Goddess,” who represented the fertility of the sea. Fish were sacred to her, and it is said that people were forbidden from eating the fish near her temple. Like the Weeki Wachee mermaids, she encouraged reverence for marine life. Mermaids also have a Cape Fear connection. As it turns out, lore suggests the Cape Fear River is watched over by mermaids — though not at the coast. The Cape Fear begins in Moncure, North Carolina, at the confluence of the Deep River and the Haw River. There, a small sandy area became known as Mermaid Point. It’s said that in the 18th century, patrons of nearby Ambrose Ramsey’s Tavern reported hearing mermaids sing in this area, but that they vanished from sight when the tavern’s patrons approached. These Cape Fear mermaids were said to have migrated upriver from the ocean, much like sturgeon and striped bass, so perhaps some do remain here, watching over our alligators, shad and herring.

The morning of the first mermaid visit was festive. The mermaid breakfast was full of families feasting on ocean-themed doughnuts from local institution Wake-n-Bake, and aquarium educators wore shiny scaled leggings. A mermaid magically appeared in a seashell-encrusted throne by the large aquarium where the show was to take place, and she met the children one by one and answered their questions: “What do you eat?” Seafood salad. Are you real? Yes. How can you tell a real mermaid from a pretend mermaid? Real mermaids live at Weeki Wachee. (Truth be told, she was discreetly wheeled out beforehand because nothing hobbles the ability to maneuver on land like a fishtail.)

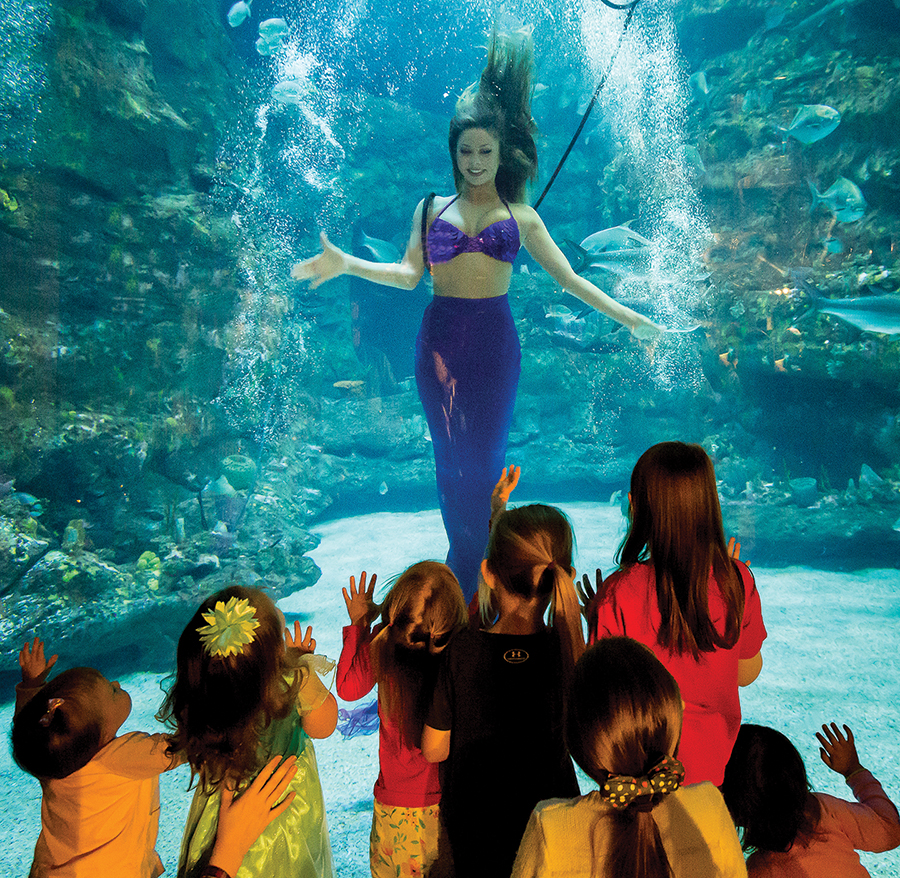

Once in the water, the mermaids were mesmerizing. They swam in circles, glided, twirled, blew kisses, all while swimming among and in the aquarium’s Cape Fear Habitat tank. The tank was full of sea creatures like small sharks, which appeared to ignore the mermaids, and groupers, which were curious about the mermaids’ glittering bikini tops. The mermaids were beautiful, yes, but the strength required to swim in 75-degree water, in a mermaid tail, for a quarter of an hour while occasionally breathing through an air hose was impressive. The mermaids always looked so relaxed. Occasionally a child would place a hand against the aquarium, and a mermaid would place her hand on the other side of the glass. They’d appear to touch, a lovely gesture full of delight and longing. Too soon, the mermaids ascended to the top of the tank in a cascade of bubbles; the show was over. There was a moment of sadness in the crowd. They were so lovely, so magical, and we all wanted to be mermaids and swim in the dreamy dark blue sea.

As the crowd broke apart, I wandered around the aquarium from tank to tank. I watched the jellyfish blossom as they moved through the water. Stinging nettles trailed their long, hypnotic tentacles behind them like mermaid hair. I stopped by the seahorse tank and watched these strange creatures, as surreal as the lovechild of Louise Bourgeois and Tim Burton, motor themselves through the water with tiny fluttering fins on their backs and steer with even tinier fins on the sides of their heads.

One little girl was surprised to discover that seahorse dads are the ones who carry and have the babies. “They look like mermaids,” she said, and wandered back to the big aquarium to look at the Moray eel. It was impossible to look at the sea creatures in the aquarium and not wonder, as we did with the mermaids, what they ate, how they breathed, how they were able to propel themselves in our vast oceans.

Each tank inspires a similar awe. I once watched a young boy learn from one of the many well-trained volunteer educators about horseshoe crabs’ importance to birds like the red knot, which travels nearly 10,000 miles during migration, fueled in large part by horseshoe crab eggs. “They even have blue blood,” the volunteer said. “Would you like to touch its shell?” The man cautioned his boy to be gentle. One small hand unfurled, and he petted the crab’s brittle brown armor, seemingly aware of his human power over this spiky, fearsome-looking sea creature.

Though the mermaids have returned to their home in Florida (until the next tour), there’s still a lot to witness at the aquarium. There’s Luna the albino alligator, a rarity as alligators with albinism rarely survive 24 hours in the wild. You’ll see baby loggerhead sea turtles — just like the ones that nest on Topsail Island — and learn about the hazards they face. Lights on the beach disorient them and put them in harm’s way. Under water, single-use plastic bags look like the jellyfish the turtles’ love to eat, and once consumed, can starve them. Monofilament lines, like discarded fishing line, can entangle them. The aquarium staff makes sure that visitors know of problems, and also offer them helpful actions. (Turn off beach lights at night; put fishing line in the trash; bring a cloth bag to the grocery store. Encourage others to do the same. It pleases the mermaids.)

I wasn’t sure about a mermaid’s purpose at our aquarium, but it’s clear she serves the same purpose today as she did during her days in ancient Syria: to share a message of education and conservation. The idea, fantastic as it is, that you might see and speak with a mermaid is astonishing as a manatee inviting a small group of humans over for high tea. (Aquariums take note: I propose Man-a-teas next.)

Author Virginia Holman, a regular Salt contributor, teaches in the creative writing department at UNC Wilmington.