A behind-the-book look at Taylor Brown’s forthcoming novel The River of Kings

By Taylor Brown

It was March 2002, and the Altamaha River was running high and cold and dark, grumbling at its banks. This was Georgia’s “Little Amazon,” a 137-mile serpent of fresh water that slithered and kinked across the state, delivering the alluvium that helped build the sea islands of the Georgia coast — my birthplace. There were bald eagles here, glaring from their roosts, and alligators sunned themselves along the bars. Old-growth cypress trees stood tall as castle turrets, and the depths were storied for century-old sturgeon, some the size of ships’ cannons.

I was 21 years old, an English major at the University of Georgia, and this was my spring break, a three-day paddle trip down the Altamaha with three of my closest friends. At that time, this was not really my idea of fun. I was an Eagle Scout, but a bad one. Having just attained drinking age, I had other pursuits. But my buds were going, and I went along.

That morning, with the dawn mist lying heavy over the water, and my head cloudy with sleep, the current had seemed to suck me along, accelerating my boat faster and faster, toward the bank, until I met a dead cypress tree at ramming speed. The kayak flipped, and I was doused in cold, cold darkness. Later, hunched over shivering in my righted boat, hand-pumping river water from between my legs, I really wished I were on a beach somewhere. Of course, I had no idea that this trip would, more than a decade later, lead to my second novel, The River of Kings, in which two brothers deliver their father’s ashes down the river of his birth, this river.

“Hunter, the younger, steps knee-deep into the current, and he can feel the weight of it pulling at this calves and ankles, the dark pull that is like an ambition. The spring rains charge down the dark swales of the Appalachian foothills, rumbling in wider and deeper confluence, birthing rivers that slither for the sea. Midway, they tumble and crash over the Fall Line, the belt of shoals and waterfalls and hydroelectric dams that marks the lost edge of the continent, past which the state of Georgia was once the bottom of a prehistoric sea. The fossils of ancient corals and mollusks are found far upcountry, and the land is full of sharks’ teeth.” — The River of Kings, p. 4

I have never thought of my work as being very autobiographical. In fact, I’ve long taken some high-nosed satisfaction in the fact that my fiction could never be construed as thinly veiled memoir. However, again and again, I find that I can trace threads of my stories back to some direct experience. On this trip, it would not be that rude dunk in the morning river, but something more sinister.

That afternoon, we stopped to rest at a bend in the river, climbing a small bank in search of shade. There, to our surprise, we found a footpath leading into the woods. At this point, we were miles from any known settlements or residences. The Nature Conservancy has called the Altamaha River one of the world’s 75 “Last Great Places,” and this lack of civilization is the main reason why. The river is undammed, crossed by roads only five times in its entire length, and in the ’90s, the state outlawed the floathouses (“shantyboats”) that once lined the riverbanks. We followed the footpath into the woods, and what we found there is just what the brothers in the novel find:

“Hunter follows, a little behind, careful of his own feet, the sound they make. The wind rises, swirling through the trees, leaves humming on every side. They are fifty yards down the path when they cross a small creek and find an alligator gar lying across the trail, gutted. It is four feet long, a torpedo of a fish with hard, enameled scales and outsized teeth. A living fossil, dead. A warning. A black vent has been sliced in the yellow belly, the innards scooped out and left to rot in a ropy pile. Maggots glisten in the cavity. Flies abound, ticking like tiny robots across the exposed viscera. It smells like it looks.

Lawton lowers himself to one knee and cocks his head, examining the work. Hunter starts to say something but Lawton’s blue eyes cut toward him, killing the words in his chest. Now Lawton rises, and on they move. The path winds deeper into the woods, zagging around deadfalls of old timber, crossing shallow streams where Lawton kneels for prints. Hunter is breathing hard now, like he would after a standing block chop. He looks down and finds the hand-ax at his side. He doesn’t even remember taking it from the boat.

Another hundred yards on and both of them stop.

Before them two saplings stand arched over the path, their upper reaches lashed to form a makeshift arbor. The skulls of small animals and fish dangle from the branches on lengths of fishing line, a crop of cruel ornaments trembling in the breeze. Their hollow sockets sway this way, that way, guarding the path before them. Hunter reaches up to touch one — a raccoon’s skull maybe, or a large gray squirrel — then doesn’t. When he looks down again, Lawton has a gun.” — The River of Kings, p. 280

We did, too. A tiny .22-caliber revolver. Because we were fearless and dumb (there is a reason why boys this age are sent to fight wars), we explored the shed we found. It was empty, thank God. But the question of what it was there for, and why its owners had tried so hard to ward us away, has always haunted me. That mystery became the seed that would birth The River of Kings.

I wrote it as a short story first, “Riverkeepers,” which was published in Chautauqua, edited by graduate students from Wilmington’s own UNCW Creative Writing program. But the story felt bigger than a mere 17 pages. Here was a river with its own mythology, complete with conquistadors and highlanders, 7-foot alligator gar and catfish the size of mermaids. A river rumored to a harbor a sea monster not unlike the one in Loch Ness, reported since earliest times:

“A creature trapped here, perhaps, when the prehistoric seas receded. Probably just a line of sturgeon surfacing — only that — but their father believed it something more. He believed the stories of the old-time timbermen, who described a thing darker, more sinister.

“Ridge-backed.” His broke-knuckled hand cruised before their boyhood eyes. “Got a head like a Tyrannosaur, teeth like one, too. Flippers the size of ship’s oars. Swims like a dolphin, up and down. Got a body round and strong as them cypress trunks they sent streaming down the canals.”

Hunter looks at the trees along the riverbanks. There is hardly any of that old-growth timber left now, a few ancient survivors that pose for photographs, a centuries-old myth trolling the waters they once guarded.” — The River of Kings, p. 17

Yes, here was a river that had abetted the deforestation of the state, carrying timber rafts the size of basketball courts down to the coastal sawmills. A river endangered itself by pulp mills and nuclear power plants. A river as beautiful and wild and savage as anything left on this Earth.

Here was a book.

I began, and so did a number of research trips with men I regard as my brothers. Whit Dawson, Taylor Davis, and the photographer Ben Galland (Island Time and Island Passages). These are friends I have known since elementary school, who were there on those early paddle trips, and whose love of the river is undiminished. We would search the river for landmarks I was writing into the book, visiting Alligator Congress and Rifle Cut and Stud Horse Creek. We would witness what we thought for one surreal moment to be the Altamaha-ha herself — and which, in fact, turned out to be nearly as strange: a large feral hog swimming across the river. We would be trapped far upriver by a grounded boat and have to navigate the night river with nothing but flashlights, watching the bright jewels of alligator eyes burn along the banks. We would search the river for narrow-gauge rails and ancient logging equipment and thousand-year-old virgin cypress.

“They round a spiky thicket of palmetto and before them a stony colossus roars skyward from the earth, a cypress as giant-footed as a house, the root base knuckled and tapered like ten trunks grown all into a single primeval missile. Woody stalagmites, man-tall, stand like cloaked old guards on every side, and a dark cloud of big-eared vesper bats may or may not be hanging asleep in the tree’s hollows.” — The River of Kings, p. 88

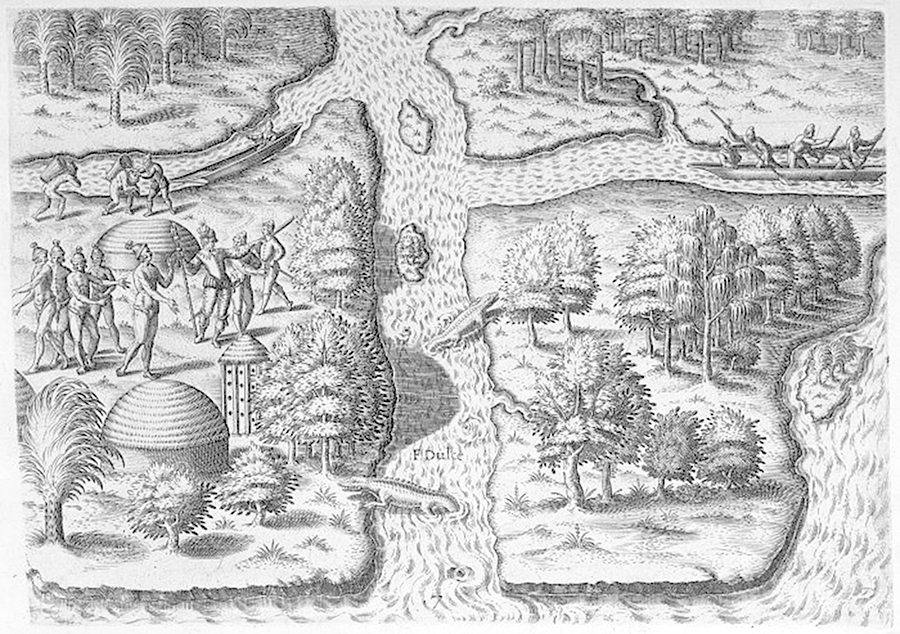

But something was missing, or perhaps waiting to be found. I would discover it in the form of Jacques Le Moyne de Morgue, a French botanical painter who accompanied the 1564 expedition to found the Huguenot settlement of Fort Caroline — the first permanent European fort in what would become the modern-day United States, predating St. Augustine by one year and Jamestown by four decades. Le Moyne (“The Monk”) would be the first European artist to capture the flora, fauna and — most intriguingly — the natives of this New World.

“They waded ashore to greet the natives, the iron barrels of their arquebuses marching like organ pipes, their swords banging against their legs. The surf exploding against their knees. The natives waited on the beach with round eyes, white as bone, and Le Moyne could smell them as he neared: an animal musk, smoky and wild. They surrounded the white men in twitching rings, their limbs long and powerful, their skin queered with inks and mazelike designs. They had long fingernails, sharpened into claws, their ears yoked with inflated fish bladders. Their eyes darted about, quick as baitfish. Like children they reached out, shyly, their brown fingers seeking the godlike torsos of the landing party’s armor, the long black beards that pointed their chins.” — The River of Kings, p. 9

The events at Fort Caroline are touched by mystery, gleaned as they are from the written narratives of those involved, the facts of which are perplexing, even contradictory. But one thing is now certain: The fort was not located on the St. Johns River near modern-day Jacksonville, Florida, as scholars so long believed. It was, more likely, built at the mouth of the Altamaha River. Friends of mine have looked for Fort Caroline themselves, studying satellite maps for a ghostly triangle of newer-growth trees — indicating the outline of a fort — and finding one.

I would weave in the story of Fort Caroline with that of the brothers, braiding together story lines spaced more than five centuries apart. I based many of the historical chapters on scenes from Le Moyne’s own work. After completing the manuscript, I needed to find a Renaissance French scholar to check my phrasing and usage.

Christopher Rhodes — my incredible agent and friend — put me in touch with Dr. Scott Juall, associate professor of French at UNCW. Here is where destiny seemed to intervene. As it turned out, Juall had just returned from Paris, where he had presented on the travel narratives of Le Moyne and other characters from the novel. Jacques Le Moyne and the French experience at Fort Caroline are studied by a mere handful of scholars — I’d had no idea that one of them lived in Wilmington!

Today, our connection feels fated, but at the time, I was coated in a nervous sweat. What would this scholar, who had dedicated himself to the study of early modern European travel narratives, think of my fictional interpretation of the material on which his career was built? What glaring errors would he uncover, gutting my manuscript like that gar in the woods?

The answer would come in late March of last year. I had been on tour with my first book, Fallen Land, a Civil War-era novel, for nearly three months, a barrage of readings and interviews and appearances — all while writing the first draft of a new book and running the wholly separate business that pays my bills. I was run ragged, harried, living close to my bones. I was changing clothes in a gas station parking lot on Franklin Street in Chapel Hill, manuscript in hand, prepping to meet my editor in person for the first time. The glorious life of a novelist.

Then the email from Juall arrived. He had just finished reading the French chapters of the novel. He found them excellent, he said. He liked how I had imagined the attitudes and dialogue of the characters, fleshing out the insights from the narratives in provocative and sometimes comical ways.

Relief hit me like a flood; I was almost giddy. My blood ran high and bright. So many months of work go into a novel. So many late nights and early mornings, so many hours of doubt and sacrifice. Triumph, when it comes, is sweet.

Over the coming months, Juall would prove an invaluable supporter of the book. He would instruct me on Renaissance-era French insults (“What weak testicles”) and direct me toward 16th century accounts of flying alligators and sea monsters witnessed by early explorers. He would put the novel on his syllabus and invite me to guest-lecture to his class.

But all that was to come. On this morning, I was now running late for brunch with my editor. I parked down the street and made a mad dash for Crook’s Corner, breathless with anticipation, my messenger bag thumping against my back. I was propelled as by the river itself, buoyed with gratitude for those brothers, both real and written, who have accompanied me down such strange and wondrous paths.

“They slide their boats into the water, finding the dark muscle that pulls them along, and Hunter watches his brother become a shadow of himself in the mist, amorphous as story or myth, a storm rolling slowly downstream.” — The River of Kings, p. 119

Taylor Brown grew up on the Georgia coast. He is the recipient of the Montana Prize in Fiction. His first book, Fallen Land, was excerpted in Salt last winter. His second book, The River of Kings, is forthcoming from St. Martin’s Press this March. He lives and writes in Wilmington. www.taylorbrownfiction.com