Becoming the Uncarved Block

Story & Photograph By John Wolfe

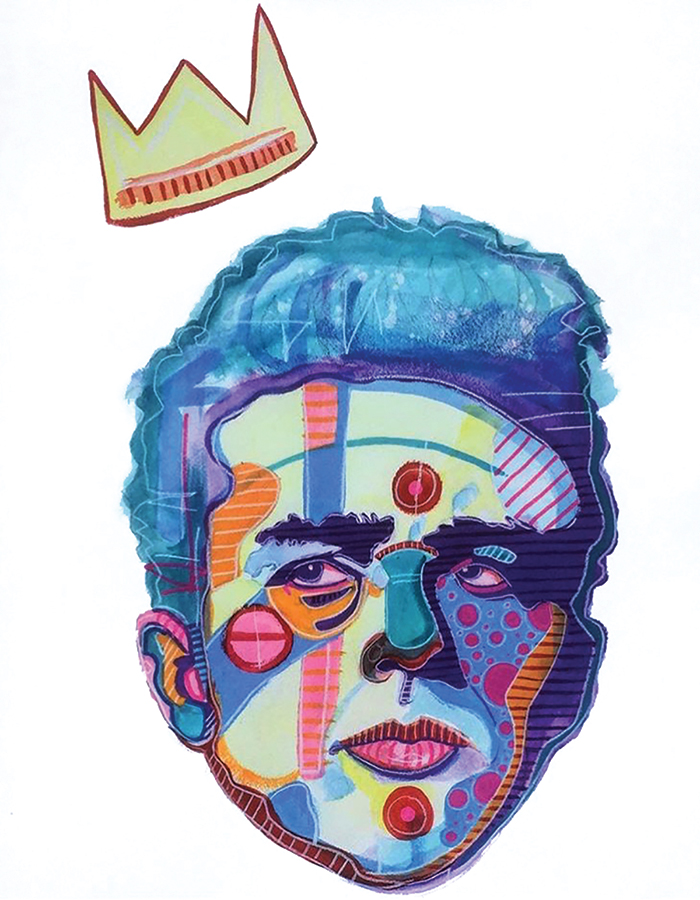

Artist Nathan Verwey has big plans for the “Art of Our Time”

DISCLAIMER

Before I get too involved in describing how Nathan Verwey makes art, remember the opening lines of the Tao Te Ching: “The way that can be spoken of is not the true way; the name that can be named is not the constant name.” It would be difficult, if not impossible, to capture in words what Nathan does using paint, because it’s like taking a still photograph of a child at play — you might succeed in getting an angle of it, but the actual act is alive, and so different from moment to moment that each iteration is a unique thing. That’s almost the whole point.

THE ARTIST HIMSELF

Verwey is tall, dark and handsome with a hint of danger, a man with the appeal of a jaguar, with a plume of umber hair above deep brown eyes and worn Converse All-Stars. He’s from Wisconsin, originally, and came to Wilmington to pursue acting in 2007. That’s when he started painting, using an easel kit his father gave him as a Christmas gift. He “got serious” about painting five years later, the first time he painted on a wall that the public would actually see. But he’s been a creator for as long as he can remember. For him, creation is a space of peace and stillness, somewhere he can escape his own constantly racing mind. He is a happier person when he works every day.

Verwey is tall, dark and handsome with a hint of danger, a man with the appeal of a jaguar, with a plume of umber hair above deep brown eyes and worn Converse All-Stars. He’s from Wisconsin, originally, and came to Wilmington to pursue acting in 2007. That’s when he started painting, using an easel kit his father gave him as a Christmas gift. He “got serious” about painting five years later, the first time he painted on a wall that the public would actually see. But he’s been a creator for as long as he can remember. For him, creation is a space of peace and stillness, somewhere he can escape his own constantly racing mind. He is a happier person when he works every day.

THE WORK

He works like a miner following a vein of gold through a rocky outcrop. When he finds a thread, he pursues it until it has run its course; by then, he might have stumbled across something else, so he’ll go sideways for a while and follow that thread. But it always leads him back to where he began, he says: “Everything in life is a cycle.” He sees himself not as a maker of the things he creates, but as a conduit that allows them to happen.

Like Picasso said, artists are the best truthful liars. We are drinking coffee and talking about René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images, a painting of a pipe with the caption, “This is not a pipe,” in French. “An artist’s job,” Verwey says, “is to be truthful to themselves, and speak to that nature. Even though it’s going to be a lie, regardless of whether it’s a truth or not,” to be “unabridged and honest,” which is “a terrifying thing to do.” Artists, according to Verwey, “create energy and store it inside something until somebody else comes across it.” When a piece connects the artist and audience, causing synapses to fire sympathetically from an exchange of thought, that is what Verwey considers success.

THE CONTEXT

He wants to paint a mural on a five-story building. He loves working big. When he paints a mural he feels like a bird; the passage of time is both real and irrelevant. He loves how art on the street already has an intrinsic juxtaposition — bright colors amid the grit — and how it’s on display for no cost 24/7 (with no holidays), accessible to all. Street art is “the art of our time,” he feels. An artist can paint a masterpiece on a wall — something that ought to hang in a quiet gallery — and weather and time will take it away. To take it so seriously is silly, he thinks. Art is ephemeral. To frame it, to preserve it, to worship it, is to keep a butterfly in a cage, to lock up something that was intended to beat as freely and finitely as our own hearts. To quote the Tao, again: “It is because it never attempts itself in being great that it succeeds in becoming great.”

John Wolfe studied creative nonfiction at UNCW. He can be found online at www.thewriterjohnwolfe.com.