In Search of the Maco Light

Halloween hokum or Joe Baldwin’s ghostly light? Our man who has seen the light investigates

By Chris E. Fonvielle Jr. Photograph by Andrew Sherman

October. The time of year when the oppressive heat and humidity of the long Southern summers finally begins to subside, signaled by verdant vegetation changing colors and golden leaves gliding softly to the ground on cool autumn breezes. The end of the month brings Halloween, when allegedly the space between the living and the dead narrows to a thin veil. Stories of spirits crossing over between the supernatural realm and the natural world are retold again, as they have been for thousands of years. Not many people would admit to believing in ghosts for fear of ridicule, and yet they might concede to being intrigued by the possibility of their existence. Too many reliable people have witnessed strange phenomena that defy rationalization.

If a Ph.D. in American history provides even a modicum of credibility, then count me among those who have witnessed paranormal things I cannot explain. The first time was in 1969, when I was 15 years old, in my hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina. Two friends and I saw what can only be described as a ghost in Thalian Hall, one of the nation’s oldest performing arts centers that opened in 1858. I grew up hearing ghost stories from my mother, a TV talk show host and a marvelous actress, and other Wilmingtonians who performed on stage at Thalian Hall or were associated with the theater in some way. Although it was the 1960s, I was not hallucinating when I saw the apparition of a tall, thin man in Edwardian dress, replete with frock coat and knee-high boots, in the main gallery on a late Sunday afternoon in May. My two friends Sam Eckhardt and Tom Saks also witnessed it, describing in detail exactly what my senses encountered.

Mystified by our inexplicable experience at Thalian Hall, we hoped to recapture the nervous excitement we felt by visiting Maco, an unincorporated rural community 14 miles west of Wilmington, and the site of the Lower Cape Fear’s most famous ghost story. For more than 100 years people reported seeing an amber-colored light, like a flickering lantern, swaying gently back and forth as it moved slowly up and down the tracks of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad near Hood Creek (also known as Hood’s Creek) in Brunswick County. Yet all efforts to discover the source of the Maco Light, as it came to be popularly known, proved futile, and then one day it simply vanished. Before it did, however, I saw it two times.

Before the Civil War, what became Maco was part of Rattlesnake Grade along the Wilmington and Manchester Railroad in Brunswick County. Trains traveling west out of Wilmington ran mostly on flat tracks until they reached Hood Creek, where the ground began rising 22 feet over a 3-mile stretch to Rattlesnake Creek. Railroad men referred to it as Rattlesnake Grade. In 1870 the Wilmington and Manchester Railroad was purchased and reincorporated as the Wilmington, Columbia, and Augusta Railroad. The line eventually merged with the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, later renamed the Seaboard Coast Line. From the early 1870s until Maco was established, locals called the sparsely settled area Farmer’s Turnout.

Maco is a derivation of Maraco, one of half a dozen farming communities established in southeastern North Carolina by Hugh MacRae of Wilmington shortly after the turn of the 20th century. MacRae was inspired by an ambitious “Southern Colonization” movement to develop agribusiness districts settled by European immigrants. His Carolina Trucking Development Company established Castle Hayne in New Hanover County for Dutch, Belgians, and Hungarians; St. Helena in Pender County for Italians; New Berlin in Columbus County for Germans, and three other colonies with plans for their migrant residents to grow a wide variety fruits, flowers, and vegetables.

In 1908, MacRae founded his sixth colony, Maraco, on a 10,000-acre tract in west Brunswick County for immigrants from northern Italy. By the following year, Maraco boasted a railroad station on the Atlantic Coast Line, a schoolhouse, and a Catholic church. Yet it apparently failed to attract many Italians or other Europeans, as the sandy soil was not conducive to growing much of anything but scrub oak and pine trees that already dominated the landscape. The Appomattox Box Shook Company built a sawmill mill there, but the community, which locals began calling Maco by 1917, never fulfilled MacRae’s vision of a progressive, Italian-based farming district. Instead, Maco became famous for its ghost light.

Legend has it that in 1867 or 1868, a tragic nighttime train accident near the trestle that spanned Hood Creek led to the death by decapitation of a railroad conductor named Joe Baldwin. According to most versions of the story, the caboose in which Baldwin was riding became uncoupled from the locomotive and freight cars, only to be rear-ended by a second train following closely behind. Baldwin tried desperately to prevent the crash by frantically waving a lantern in an effort to warn the engineer of the oncoming train, which speedily approached, of his predicament, but to no avail. The resulting smash-up severely damaged both the second train’s locomotive and Baldwin’s car. It also wrenched from Baldwin’s hand his lantern, which was hurled into swampy ground near Hood Creek. There it continued to burn brightly for a while, and then faded out, as did Joe Baldwin’s life. Rescuers rushed to Baldwin’s aid, only to find his broken body among the twisted wreckage. His head, severed in the collision, allegedly was never found.

Shortly after the disastrous mishap, residents of Rattlesnake Grade reported seeing an inexplicable light that emanated near Hood Creek, and then moved up and down the railroad tracks. It appeared spontaneously during the night, sometimes soon after the onset of darkness and sometimes in the predawn hours. The light did not come out every night, and more often than not it did not show at all. When it did appear, the light seemed to hover about five feet above the ground, swaying gently from side to side as it slowly or quickly advanced, and then retreated along the tracks before disappearing near the trestle. The most plausible explanation for the mysterious glow, locals came to believe, was that Joe Baldwin had returned from the dead to search for his missing head, without which he could never truly be at rest.

The earliest known and most graphic published account of the Maco Light appeared in The State magazine in 1934. In “And the Light Goes On,” Charles N. Allen wrote that the strange story prompted him to investigate it more fully. In the end he offered the most vivid account of the phenomenon. “A mile or more down the right-of-way there is a flicker over the left rail, as if someone had struck a match,” Allen wrote of his personal encounter:

“The eerie-looking thing sways a little and begins creeping up the tracks. Your eyes are magically glued to its movements. The thing comes on. It becomes brighter as its momentum increases. Then it begins dashing toward you with incredible velocity. Paralyzed, you just stand there waiting for the thing to rend you to pieces, but it never reaches you. It comes to a sudden halt fifty or seventy-five yards from where you are standing. It glares at you for a moment like a fiery eye, then it speeds rapidly back down the tracks. It stops now where it first made its appearance and glows ominously there like a red moon in miniature. Then it vanishes into nothingness.”

The publisher of The State admitted being incredulous at first of Allen’s far-fetched story upon its submission for publication. He checked it out thoroughly, only to be told by several Wilmingtonians that they had seen the Maco Light “a number of times.”

News of the Maco Light spread quickly across North Carolina. The Robesonian published an account of five men from Lumberton who visited Maco on the night of July 29, 1940, to try and uncover the “mystery of [the] moving light seen from Seaboard railway tracks.” In August 1941, the editor of the Statesville Record and Landmark wrote that, “according to tradition this light, famously known in that vicinity as ‘Uncle Joe’s lantern,’ has attracted excursionists to the scene for half a century, maybe longer.” Indeed, Mrs. Lee Skipper Mintz, who had lived at Maco for 65 of her 83 years in 1964, claimed to have seen the light on a number of occasions, the first time when she was only 5 or 6 years old.

Louis T. Moore, secretary of the Wilmington Chamber of Commerce and a collector of Cape Fear stories dating back to colonial times, helped popularize, if not create, the story of Joe Baldwin in a 1948 Wilmington Morning Star article, “A.C.L. Favorite ‘Ghost’ Story.” Recognizing that nothing attracts interest (or tourists) more than a tale from the supernatural, Moore wrote that the Atlantic Coast Line, like other rail lines, “has its favorite ghost or ghost story,” but in the case of the Maco Light, the “ghost exists,” he declared.

According to Moore, former President Grover Cleveland learned of “Joe Baldwin’s Ghostly Light” while traveling up the Wilmington, Columbia, and Augusta Railroad from Florida to Washington, D.C. while on a Southern tour shortly after he left office in 1889. As the train approached Wilmington, it made a brief stopover at Farmer’s Turnout to take on fuel and water. The day was balmy, encouraging Cleveland to disembark his car to get a breath of fresh air. While strolling along the tracks, he noticed a brakeman carrying two different color signal lanterns, one green and one white, and asked about them. He was told that they prevented railroad engineers from being deceived by the “ghostly weaving of the Joe Baldwin light.” Subsequent accounts said that President Cleveland actually saw the light, but that was not possible as his train passed through Farmer’s Turnout about eight o’clock in the morning on April 5, 1889.

Moore also assert that, back in 1873, a second light materialized “shining with the brightness of a 25-watt electric light bulb,” and that the two lights would pass each other going in opposite directions along the railroad tracks. An earthquake that shook the east coast in 1886 temporarily halted Joe’s jaunts, but his light soon reappeared. “Folks knew then that Joe was again in search of his head,” Moore maintained. He also wrote that a U.S. Army machine gun detachment from Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, encamped at Maco “to try and solve the mystery, or at least perforate it,” but there is no evidence to support the claim.” There is no evidence to support it. Moore rewrote his newspaper story as “Joe Baldwin’s Ghostly Light at Maco” for his popular book, Stories Old and New of the Cape Fear Region, first published in 1956.

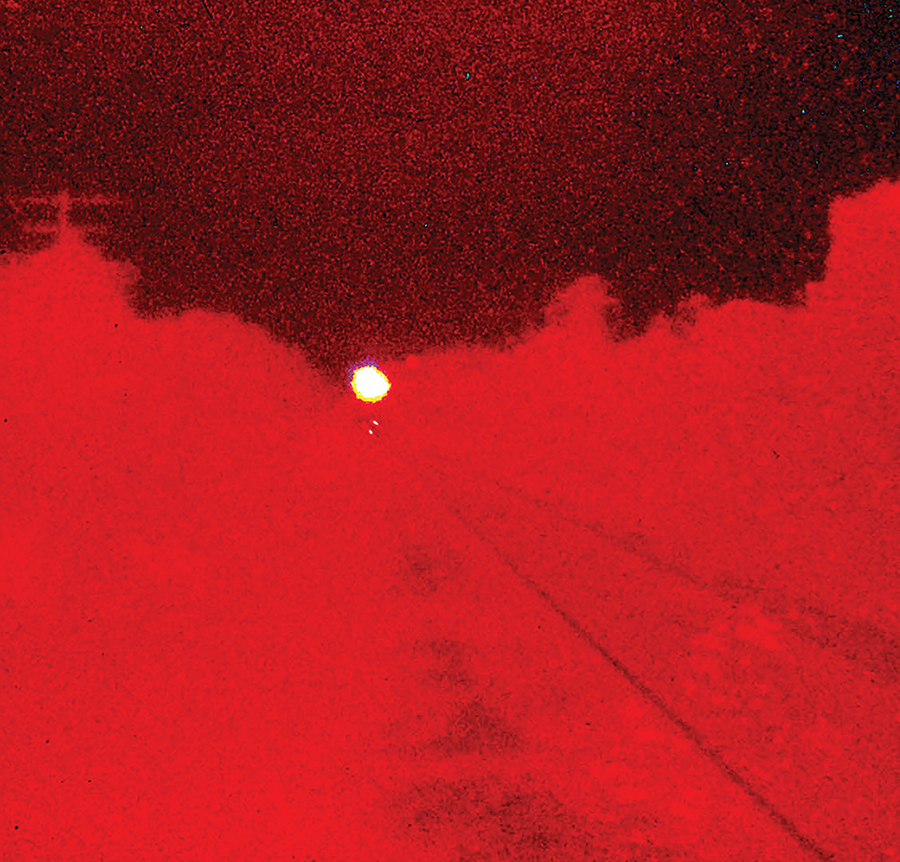

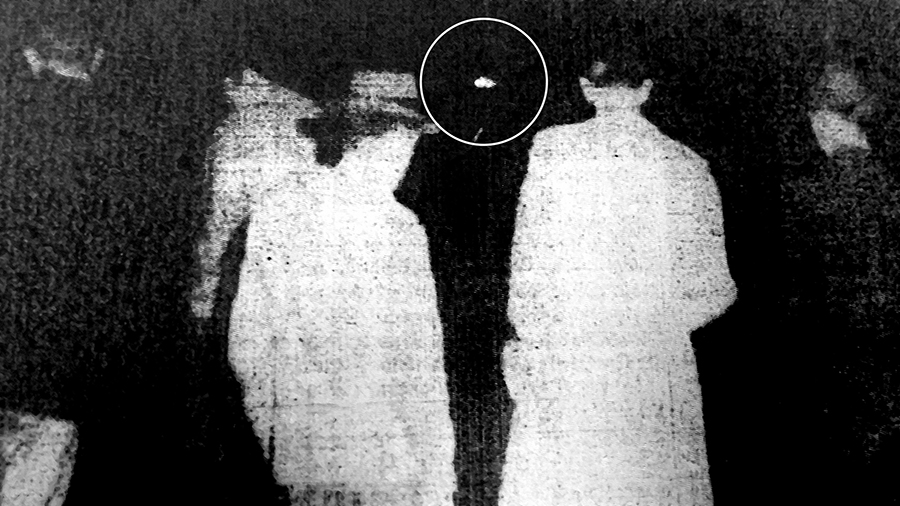

The Maco Light received noteworthy national coverage when Life magazine published the “true ghost story,” including a photo illustration of the light, in October 1957. The following month, a group of reporters from the Wilmington News took a grainy black and white photograph of a distant glowing object along the darkened railroad tracks at Maco, one of only a few extant images of the phenomenon. Many eyewitnesses — regular folks, geologists, electronic engineers, paranormal explorers, and others — posited theories as to the origin of light that ran the gamut from the reflection of car headlights to swamp gas, phosphate fumes, and a real ghost. People had seen the Maco Light since at least the mid-1880s, years before the advent of the automobile, and a drivable road from Wilmington to rural communities in west Brunswick County, including Maco, was not even constructed until 1918. Moreover, no scientist could explain the relative containment of the glowing orb or its regular movements only along the railroad tracks.

In 1964 the Southeastern North Carolina Beach Association invited Hans Holzer, proclaimed as “one of the world’s most distinguished authorities on ‘ghostism,’” to visit the area in an attempt to solve the Maco mystery. The group’s executive director characterized Joe Baldwin as “the most popular ghost in America today.” Holzer’s acceptance and resulting publicity attracted many hundreds of people to the light site in the days leading up to his arrival and during his treks to Maco in early May. When the light failed to make its appearance, Holzer blamed the large crowds for keeping it away. Nevertheless, he declared the “physic phenomenon” the spirit of Joe Baldwin. “There is no other explanation,” he stated to enthusiasts at a public address in Wilmington, during which he sold many copies of his first book, Ghost Hunter.

Perhaps it was Hans Holzer’s declaration that inspired Tex Lancaster, a country music guitarist who had played on Wilmington’s first TV station WFD back in 1954, to write and record “The Legend of Old Joe Baldwin” ten years later. In 1965 Grant Turner, a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame, released “Maco Light” on Chart Records out of Nashville, but it failed to chart as a hit. Thirty years later, Wilmington musicians Rob Nathanson and John Golden co-wrote and recorded “The Light at Maco Station,” a combination train song and ghost story, for their album Cape Fear Songs. Real or not, Joe Baldwin made an impact on American pop culture.

In every myth and legend there is an element of truth, and such is the case with the Maco Light. While researching antebellum North Carolina railroads for his Ph.D. dissertation at UNC Greensboro in 2004, James Burke discovered an account of the accidental death of Charles Baldwin, on the Wilmington and Manchester Railroad, at Rattlesnake Grade near Hood Creek on the night of January 4, 1856. According to a report in the Wilmington Daily Journal the following day:

“Some defect in the working of the pumps of the Locomotive engaged in carrying up the night train going west from this place, the Engineer detached the train and ran on ahead some distance, and in returning back to take up the [mail] train again, came back at so high a rate of speed as to cause a serious collision, resulting in some damage to the train. The most painful circumstance connected with the affair is that Mr. Charles Baldwin, the conductor, got seriously, and it is feared, mortally injured, by being thrown from the train with so much force as to cause concussion of the brain.”

Charles Baldwin, a 38-year-old New Yorker who had moved to Wilmington several years earlier, died on January 7, 1856, as a result of his injuries sustained in the crash. He was buried in Oakdale Cemetery in Wilmington the following day. Sadly, the location of his grave has been lost. Despite his best efforts, Burke found no record of a Joe Baldwin linked to Wilmington or the Lower Cape Fear.

Somehow, some way, the distant public memory of Charles Baldwin’s death in the unfortunate train accident at Rattlesnake Grade in 1856 became discombobulated with “Uncle Joe’s lantern” and the headless ghost with Louis T. Moore’s telling of the story first published in the Wilmington Morning Star 92 years later. Joe Baldwin or no Joe Baldwin, the Maco Light was seen by thousands of people until the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad pulled up the tracks in 1977, after which time it vanished.

Along with a small group of friends, I saw the Maco Light twice in the summer of 1969. The first time it appeared as a small glowing orb that seemed to sway from side to side along the rail line near Hood Creek, several hundred yards from our position to the west. The second time we visited the site the light moved upon us so quickly, and radiated such a powerful illumination, that we could see its reflection on the hood of our car. It soon moved back down the tracks, as we stood watching in exhilarated disbelief.

Jim Jochum captured the most compelling evidence of the Maco Light’s existence. He visited the site frequently with his family when they traveled from their home in Winston Salem to Bolivia near Maco, where his first wife’s parents lived. Jochum first saw the light in 1953. Five years and many viewings later, he took three spectacular photographs of the light using an infrared camera on a tripod loaned to him by scientist friends who worked at Bell Laboratories in Winston Salem. The most intriguing image clearly shows the light and its reflection on the railroad tracks, with the tree line and a telephone pole also visible. “The Maco Light was real,” says Jochum, now a spry 86-year-old resident of Greensboro. “I know because I saw it at least 15 times and photographed it.”

Maco never was much of a town, even less so after the North Carolina Department of Transportation rerouted and widened Highway 74/76 to four lanes in the late 20th century. Life largely passes by Maco now. Yet for decades it was the ghost capital of the Tar Heel State and the site of the Lower Cape Fear’s most famous ghost story. And if the Maco Light was not a specter, wrote noted journalist Ben Steelman of the Wilmington Star News in 2004, “why does it no longer shine?” b

Chris E. Fonvielle Jr. is professor emeritus in the Department of History at UNC Wilmington. A Civil War and Cape Fear historian and author, he received the Order of the Long Leaf Pine for distinguished service to the State of North Carolina upon his retirement in 2018. He would like to thank Jane and Doug Anderson of Port City Paranormal; Nancy Fonvielle; Jim Jochum; Rob Nathanson; Daniel Norris of SlapDash Publishing; and Joe Sheppard of the New Hanover County Public Library for their assistance with this article.