An enduring springtime ritual shared by a quartet of golf-loving friends from Charlotte to the Cape Fear

By Jim Dodson

“Without question,” says Greensboro’s Keith Bowman with a gentle smile. “It’s been quite a journey.”

“Seems like just yesterday,” agrees Charlie Gordon of Charlotte. “Has it really been that long?”

“It was just a minute ago when we first went,” adds Wilmington’s Ted Funderburk on a wistful note.

“Fortunately we have some great memories,” Charlie points out.

“And it’s not over yet,” says Bowman.

Heads bob in agreement.

And with that, the stories begin to fly like an Arnie Palmer golf ball.

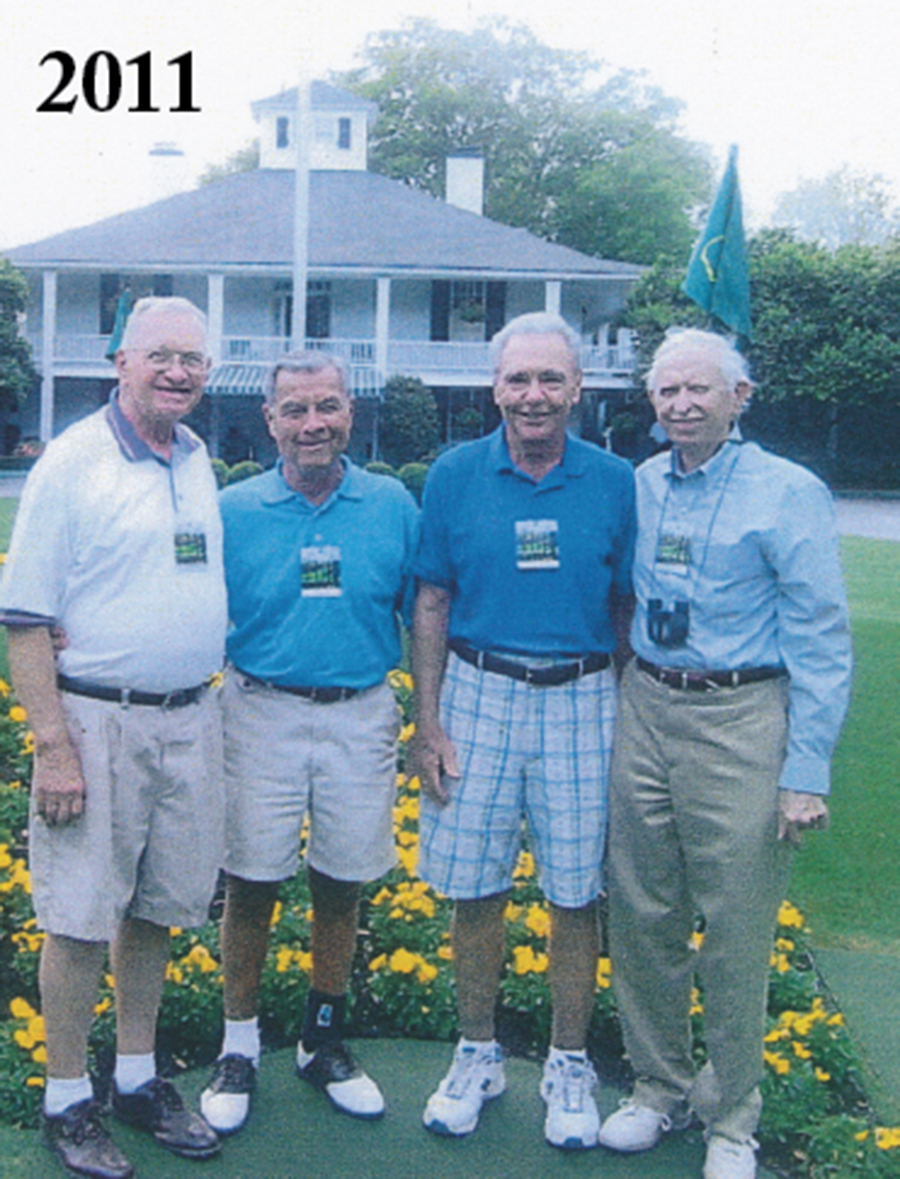

These three gents — all comfortably ensconced in their early-to-mid 80s, sit around a glass table leafing through a pair of remarkable scrapbooks meticulously assembled over more than half a century by Keith Bowman.

Like a trio of modern-day Musketeers, they are master swordsmen of a different sort who’ve enjoyed quite an adventure in each other’s company. And just like legendary companions of Alexandre Dumas’s famous novel — Athos, Aramis and Porthos — there is even a devoted fourth member of their select fellowship. Jimmie Eckard is the d’Artagnan of the group, but on this day he is at is at home in Parksley, Virginia, taking care of his ailing wife, though happy to contribute by phone.

Military service shaped all of their lives, but the swordsmen in question are in fact a quartet of golf-loving white dudes bonded till death do them part by a powerfully shared affection for each other and an annual rite of American springtime called the Masters Golf Tournament. For 58 consecutive years, they’ve faithfully attended professional golf’s most celebrated and coveted boutique event, collecting a lifetime of colorful memories and intimate brushes with the biggest stars in the game from Arnie to Tiger.

“Not bad,” quips Keith Bowman, “for fellas who aren’t millionaires — just four friends from college.”

Maybe so, but as the years of their love affair and Bowman’s magical scrapbooks reveal, their memories are, indeed, priceless.

Charlie and Jimmie grew up in Charlotte. Charlie’s dad ran a meat market and worked for the Greyhound Corporation. Jimmie’s daddy lost an arm working for Merita Breads and later ran the company’s factory shop that sold day-old bread.

Ted was something of a high school sports legend out in Matthews long before it got swallowed up by suburban Charlotte.

“We heard stories about Ted even before we met him,” says Charlie with a laugh. “A real

athlete. He played everything — baseball, football, basketball. In college he even became a tennis champion.”

Keith grew up on Bellevue Street in South Greensboro. His daddy was a fine carpenter. Around age 12, Keith and a buddy got interested in golf and built a 3-hole golf course in a field near his house. They also fashioned crude golf clubs from broom handles and wood scraps from Keith’s father’s woodshop.

“My buddy and I were fully in charge of construction and maintenance. All other kids in the neighborhood soon wanted to play it.” Not long after this, through a neighbor who ran the caddie program at Greensboro Country Club, Keith found a job caddying, riding his bicycle through town to the north side of the city on weekends and holidays. “I think I got 75 cents for 18 holes and once caddied for one of the Cones, either Herman or Ceasar, I forget which,” he remembers with a grin. “In lieu of a tip, Mr. Cone equipped his bag with a sheepskin strap that made carrying it easier — or so he thought. But that’s when I really fell for golf.”

Bowman soon acquired a real set of clubs and began playing at the public Gillespie Park and eventually carried his love of golf off to college — first to Duke University and then on to “State College” — which is how most people referred to N.C. State University back then. He planned to study architecture and structural engineering.

Charlie and Jimmie, who became good friends their final year in high school, also went off to study engineering at State.

Ditto Ted Funderburk, hoping to also be an engineer of some sort.

The four wound up in the same freshman dorm, Tucker Hall, and attended several of the same classes. They were also in ROTC together and later became roommates on and off campus, developing a friendship that bloomed like dandelions on a spring lawn.

Golf soon sealed the deal.

“I needed to take a phys ed course and found that golf was available, so I took that,” Charlie says, “and got hooked.”

“They had a driving range with wooden clubs at State,” recalls Ted, who also played his way onto the school tennis team. “That’s where I learned to hit a driver and thought, wow, this is great.” Pretty soon, he and his college chums Keith, Charlie and Jimmie were beating the ball around local municipal courses and the Raleigh Country Club, where State students were allowed to play. Back home in Charlotte they played at a course owned by local PGA star Clayton Heafner.

“Ted got good fast,” reports Jimmie from Parksley.

“He was a scratch player eventually,” notes Keith.

“No, no,” rumbles Ted good-naturedly. “The best I ever reached was three or four.”

“Better than any of us,” cracks Charlie.

“Well,” Keith picks up the story, “the point is, we all liked each other a lot and we loved to play golf and that eventually led us to plan to try and attend the Masters.”

It was 1960 before they pulled off the feat.

By then Keith had done his required stint in the Air Force and Jimmie was still in the Army, serving in Vietnam, in fact, in the early days of a distinguished 20-year Army career that would lead him to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. In his 50s he retired home to Charlotte and purchased a 19-acre orchard, and began growing apples and peaches.

By 1960 Charlie had graduated as a civil engineer, also done his required military service and was working as North Carolina’s lead Construction Officer. In time, he would rise to the post of Director of the state’s construction projects, and later become a key administrator for the Small Business Association.

Following his stint in the Army, Ted was working in Charlotte as a division engineer in the state highway department, playing a lot of golf around the Queen City. He got a promotion to Raleigh and eventually transferred to Wilmington, which suited his career and golf game just fine. In more ways than one, Eastern North Carolina became his turf.

Keith, in 1960, was working as a design engineer for Western Electric on a secret Nike missile project in Burlington. On weekends he and his buddies from work would “scurry down to Pinehurst to play No. 2. You could play all day and the price even included a shower in the locker room.” More than once, Ted drove over from Charlotte to join him.

“We were both really crazy for golf,” Keith underscores, having once captured a third-flight Carolina Golf Association tournament at Pinehurst. His handicap in those days, he reckons, was about a 16 or 18.

The college chums still shared a dream of attending the Masters Tournament someday in each other’s company.

Their timing couldn’t have been more historic. The year 1960 was a seminal moment in the growth of American golf, largely owing to the telegenic charm and go-for-broke style of a charismatic player from working class Latrobe, Pennsylvania, named Arnold Daniel Palmer.

“I loved Arnold Palmer and decided I had to see him in action at the Masters. I invited Ted to join me.” Keith remembers. “That’s when it all started for us.”

“Keith picked me up in Charlotte and we drove down on a Friday night. It was rainy and we didn’t know where we would stay. But we were young and it was a great adventure.”

At that moment the Masters was a reasonably priced affair, attended by maybe 15,000 fans on any given Masters Sunday. A daily ticket — which was still available — went for $3.50, the equivalent of $30 adjusted for inflation. Today, 60 years later, a full tournament pass that includes practice rounds and the famed par-three tournament on Wednesday goes for just under $400, if you can lay hands on one. Famously, Masters tickets are believed to be the toughest tickets in all of sports to acquire.

Keith and Ted paid $15 for the entire week but only needed them for Saturday and Sunday, a bargain considering that tickets for Saturday and Sunday, the days they mostly went, were $7.50 per day. Through the local chamber of commerce, they managed to rent a room at an Augusta boarding house and went out to the local Holiday Inn Lounge where they discovered the Hebert brothers, Jay and Lionel, the trumpet-playing Cajuns who managed to both win the PGA Championship during the day, while performing in the motel lounge at night.

“That was pretty exciting,” recalls Keith, “but we were dead tired from the drive. The next morning we woke up and realized what an awful place we’d spent the night in. It looked like it rented by the hour.”

So before heading off to the course, they arranged new digs just two blocks off Washington Road and the entrance to Augusta National. It was the home of Kitty and Quentin Moore. With only a handful of hotels and motels in the city, Augusta residents often rented out their houses and rooms to Masters patrons, as they were called. These days, local residences during Masters week routinely rent for five and six figures, many of them rented by corporations for entertaining clients.

In 1960, however, the thoughtful Moores actually moved out to a trailer in their backyard and allowed Ted and Keith to have the run of the place.

“The Moores were wonderful people and we hit it off immediately,” says Ted. So much so, the twosome — soon to be expanded to a golf foursome — wound up staying with the Moores for the next 37 years.

“That was the beginning of a great friendship. When they moved to a new neighborhood, we moved with them,” says Keith. “We watched them have kids and watched the Moore kids grow up. We grew old with the Moores year after year and even attended both of their funerals a few years back.”

History records how Arnold Palmer won his second Masters in 1960 — and went on to have the kind of year, dreams are made of capturing the US Open in extraordinary fashion later that summer in Denver and almost taking home the Claret Jug from the British Open Championship. His unprecedented popularity would begin to rewrite American golf, producing historic growth of the game.

What it doesn’t record is the joy Keith Bowman felt upon seeing his golf hero in the flesh and at his peak.

“He just captivated the galleries. There was so much excitement in the air. In those days, they let patrons bring in cameras for taking photographs after the day’s play,” he says, noting how he always wiggled his way to the front of the crowd for the presentation of the champion’s green jacket, and used his trusty Nikon camera to snap some beauties of Arnold and Winnie sharing a triumphant moment.

Maybe even more impressively, Bowman managed to shoot every Masters green jacket ceremony up to Tiger Woods, and hundreds, if not thousands, of casual shots before and after their tournament rounds. Most of the champions Keith photographed were happy to autograph their photos for his scrapbook, including a reluctant superstar named Ben Hogan. Over the years, Keith also sent his photos to a gallery of the game’s biggest stars, most of whom wrote back thanking him with personal letters.

“I took my first photo of Mr. Hogan warming up on the practice range in on April 7, 1962. Two years later, I approached him before the third round — where he shot the low round of 67 — and asked if he would mind autographing my photo of him. He said to me, ‘I’ve got work to do but come find me after the round, I’ll be happy to sign it.’ Keith did just that and Hogan not only autographed the photo but introduced him to his wife, Valerie. “We had a very nice conversation. What a classy man. It was such a thrill.”

Keith’s weren’t the only set of eyes on the Wee Ice Man, as the admiring Scots nicknamed the reclusive Fort Worth star on his way to winning the Claret Jug at Carnoustie in 1953.

“I loved watching Hogan warm up — learned a lot by just watching him,” says Ted Funderburk. “I read his books Power Golf and Five Lessons and really improved my golf as a result of seeing Ben Hogan.”

In the 1962, a large black-and-white snapshot of the massive crowds sitting on the hill by the 16th hole appeared in Life magazine. There among the faithful hordes in their Easter finery sit none other than young Ted Funderburk and Keith Bowman looking on as Arnold Palmer headed for his third Masters title, tying him with Sam Snead and Jimmy Demaret.

By 1972, Charlie Gordon and Jimmie Eckard had joined the annual spring road trip, completing the foursome for all four days. On one of Charlie’s first trips to Augusta, as an Army Reservist, he had to brief a general before racing to the airport to catch a flight to Augusta, changing out of his uniform as wife Barbara raced him to the airport. “I just made the flight and got off the plane to find a group of absolute strangers welcoming me. Keith and Ted had whipped up a little crowd just to greet me — and Kitty Moore even baked a cake for the occasion. That was the kind of fun we had.”

The first three years Jimmie attended the tournament in his uniform. “You could get a ticket half price. There was such respect for soldiers there. Everyone was treated that way at the tournament. Once you’re inside the gates, everyone is the same.”

The group typically started their tournament treks at the first green then fanned out across the course, often peeling off to follow their own favorites.

Keith stayed true to Arnie, as did Jimmie, who learned to follow Winnie Palmer, who knew the best places to stand near her man. (One story the group loves to hear again and again, told by Jimmie, is how Winnie, to stave off hunger, had stashed a piece of fried chicken in her purse. At the very moment she was discreetly removing it, she was approached by a fan. The ever-gracious Winnie politely offered her lunch to the woman, who gladly accepted it, leaving Winnie hungry.) A crack gardener who kept a large farm in Climax where he propagated azaleas, Keith snipped off pieces of a golden flowering Augusta azalea from the woods around second and eighth fairways. He took them home, soaked in water, and for years tried to get them to take root — until he was finally successful.

Jimmie Eckard also had a thing for Chi Chi Rodriguez and Lee Trevino. Charlie liked following Trevino and Gary Player.

“Trevino was such a people’s favorite,” Charlie says, launching into a memory of how he was once standing by an errant Trevino shot when the Merry Mex strode up and glared at his poor lie, removed a club and he glanced at Charlie. “Here, you better hit this shot for me.” The gallery roared. “Trevino played fast. I remember how he hit his shot and remarked to his slower playing partners, ‘C’mon, folks. Hit your shots. I’ve got to get across the river and feed the cows.’”

Ted fancied the buttermilk swing of Julius Boros and had a sweet and unexpected encounter with the two-time US Open champ one evening after play’s end. “It was near dusk. We always liked to stick around so Keith could take pictures, and Boros was relaxing at the back of the clubhouse with a drink. We started chatting — I knew he had connections to Mid Pines and Pine Needles, one of my regular golf places — and he wondered if I wanted a drink, too. He gave me his clubhouse pass and I went in and got my own toddy. We had nice long conversation.”

Ted was the group’s only drinker.

“We weren’t much into the party aspect of the Masters,” notes Keith. “Pretty calm bunch just into the golf.”

“In other words,” jokes Charlie, “dull as could be.”

How about Jimmie?

“Dullest of all,” says Ted (who gave up drinking years ago). “But don’t tell him we said that.”

One year, however, the group came across an elaborate wedding party staged in the parking lot after the tournament. Because of their long-standing friendships with the tournament’s ground staff and parking attendants, the Four Masters always managed a primo parking spot near the entrance gate.

“The wedding couple was from Texas. They had a Cadillac rigged with a set of longhorns, lots of food, flowers, champagne, even a chandelier,” Keith recounts. “They invited us to join them. We had a great time.”

In 1976, eager to have his own tickets, Jimmy Eckard placed his name on the famous Master ticket waiting list and had to wait until 1992 to get a couple of coveted passes so he could take his wife to her first Masters. While watching The Price Is Right TV show one evening, he was bothered when one of the big prizes was four weeklong passes to the Masters. “I couldn’t believe it so I wrote to Augusta to tell them how disappointed I was that fans had to wait for years to get their tickets — but here they were handing out tickets on a game show to people who might not care about anything about golf.”

He received a nice thank-you letter from the tournament office. The ticket giveaways ceased.

Over the decades, the four became so friendly with security and tournament workers, they also wound up photographed in Keith’s memory books — a friendship that came in handy more than once.

One year during the green jacket ceremony, a Sports Illustrated photographer complained to Keith for not having an official media credential and promptly reported him to security. “I’ll have to ask you to come with me,” the Pinkerton guard told him. “I’m just doing my job.” The guard then escorted him to “an even better spot to take my pictures.”

Over the past six decades, there is little the Four Masters from North Carolina haven’t seen or experienced at the world’s premier golf tournament, including weather — biting cold and rain, blistering heat waves, perfect spring evenings (often in the same weekend), not to mention aching feet, free discarded chairs, chance encounters with celebrities and more memories than one can possibly document in a pair of large scrapbooks.

“We go because we love golf and, frankly, never see each other the way we once did,” muses Ted Funderburk, who still plays a mean game around the Cape Fear.

“We go because we’ve been friends since college and this is our shared ritual,” adds Keith Bowman. “Also, it’s the Masters, the greatest golf tournament on Earth. It’s always the same but always different, some new every year. Things stay with you.”

Charlie still thinks about Arnie Palmer’s final round at Augusta, for example. This was in 2004, Arnie’s 50th trip to his favorite tournament. “It was late Friday afternoon. He’d missed the cut for the final time. I happened to be standing in front of the clubhouse when he came out and climbed into his Cadillac. The crowd saw him and began cheering. He rolled the window down and smiled. You could see the emotion on his face, how he loved that place and his fans. We watched him drive away, down Magnolia Lane for the last time as a player. I’ll never forget that.”

This year, 2018, their 59th odyssey to Augusta, was be slightly different. Jimmie’s legs could no longer manage Augusta National’s fabled hills. But a Greensboro special education teacher named Rick Haase made his second trip with the group.

Keith notes that the fellas are hoping to make it an even 60 years before their annual spring pilgrimage to Augusta ceases.

“We walk a little slower,” adds Ted Funderburk, the group’s lone single handicapper, who still plays regularly around the Cape Fear region. “But the magic is still there. It’s all about history and friendship and the return of golf in the spring.”

Jim Dodson is the editor of Salt, and the author of too many golf books to count.