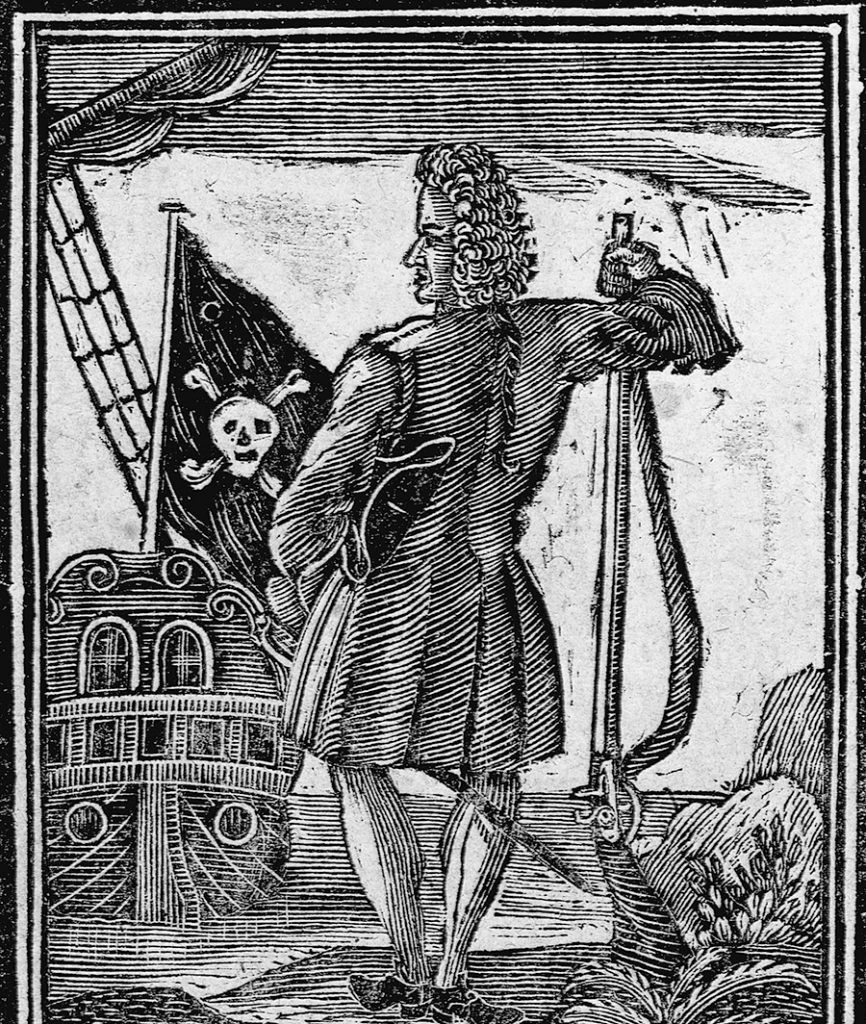

The rise and fall of dashing Stede Bonnet — like his infamous mentor Blackbeard — brought to an end the golden age of piracy, but may have scattered the first seeds of democracy

By Kevin Maurer

Pirate captain Stede Bonnet’s ship the Royal James was leaking and in need of repair.

It was August 1718, and Bonnet had just left Delaware Bay, where he captured two ships. His three-ship fleet was on its way to the Virgin Islands, but there was no way it was going to make it.

It was hurricane season, and Bonnet needed a safe place to make repairs and wait out any storms. Spotting an estuary near the mouth of the Cape Fear River (near modern-day Southport), he ordered his crew to set up a base and careen the Royal James to make repairs. Grounding the ship at high tide, the sailors heeled it over and waited for the tide to ebb, exposing the hull below the water line. Prisoners from the captured ships scraped the Royal James clean of barnacles and repaired any holes.

A few weeks later, lookouts spotted two sloops aground on a sandbar closer to the mouth of the river. Merchant men who misjudged the tide, Bonnet suspected. Easy prey for his pirate crew.

Bonnet ordered his men to take three canoes and capture the ships. As the pirates approached, they realized the ships weren’t merchants. They were British war ships. Pirate hunter Col. William Rhett’s 130-man expedition from Charleston, to be exact.

Bonnet had two choices: flee up river, or wait for high tide and escape into the open ocean. Bonnet knew victory would come to the vessel that floated first, and he gambled on his ship. It was a bad decision — one of many — that sealed his fate and led to his capture and death by hanging.

A small historical marker on NC Highway 211 near Bonnet’s Creek commemorates the battle but does not do justice to the legend of Stede Bonnet, known as the Gentlemen Pirate. While Beaufort and the Outer Banks lay claim to the most famous pirate of all — Blackbeard — the Cape Fear region is where one of the most eccentric pirates to sail the high seas was captured.

“He is intriguing because he really was a gentleman,” says Colin Woodard, author of The Republic of Pirates. “Many of the pirates were downtrodden seamen. Bonnet was wellborn and had everything to lose. He had a family. He had an estate. And yet he goes off into piracy.”

The Gentlemen Pirate

Bonnet was born in Barbados in 1688, but orphaned soon after his birth. He inherited his family’s large sugar plantation and was raised a gentleman. He joined the local militia, earning the rank of major, and married the daughter of a local planter in 1709. They raised three sons and a daughter, but he eventually left them all for the pirate life.

Historians are split on the reason. One theory points to a nagging wife, but David Moore, an archaeologist and historian with the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort, doesn’t put any stock in it. Another theory is that Bonnet was mentally ill, but Moore has a simpler explanation: money. In 1717, Bonnet borrowed £1,700 ($400,000 today). Moore said Bonnet’s financial problems likely came from a drought wiping out his sugar crop.

But Woodard thinks Bonnet became a pirate for political reasons. He was a Jacobite who supported James Stuart as king of England over the German-born King George. Pirates, according to Woodard, were in revolt. “Bonnet was part of this effort to put the Stewarts back on the throne,” Woodard says. “That would be a decent explanation.”

The true reason is lost to history. What is known is that Bonnet bought a sloop, fitted it with 10 guns and hired a crew of 70 men, whom he paid regular wages instead of splitting the loot like the other pirate captains. Bonnet named the ship Revenge and one night slipped out of Barbados.

The Gentlemen Pirate’s career started off well. He plundered four ships at the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay and took two more near New York City before returning to North Carolina. He captured two more ships off the Carolina coast, stripping one of its timber to repair the Revenge.

Bonnet then set a course for the island of New Providence — a pirate sanctuary — in the Bahamas. On the way, he ran across a Spanish warship and mistakenly ordered his crew to attack. The Spanish ship was heavily armed and damaged the Revenge, killing or wounding half the crew. Bonnet was wounded in the exchange, but it is unclear how.

“The historical record is murky,” Woodard says. “We don’t know what injury he had, but it was a serious one. He was bedridden and stuck in his cabin.”

With Bonnet in his cabin, his crew was able to outmaneuver the Spanish warship and escape to Nassau. There the pirates welcomed Bonnet’s crew, but placed Blackbeard in charge of his ship. The crew had little faith in Bonnet’s seamanship. It didn’t help that Bonnet would sometimes walk the decks in his nightgown and spent his hours tending to his personal library instead of the ship.

“They were used to dangerous living on the high seas,” Moore said of the mariner culture. “[Bonnet] was out of his element. His crew saw it.”

Eventually, Blackbeard sent Bonnet to the larger Queen Anne’s Revenge and appointed his first mate to take over the Revenge. While Bonnet was Blackbeard’s guest, the pirates laid siege to Charleston harbor and took prizes along the mid-Atlantic coast, using North Carolina as a base.

Moore said the pirates liked North Carolina because of its many inlets. There wasn’t a lot of government in the colony either.

“It was easy for them to fence goods,” Moore said.

It was also where they could get a pardon from Gov. Charles Eden. King George signed his Act of Grace in 1717, which offered amnesty for any acts of piracy committed after the Queen Anne’s War. It extended for one year. When Bonnet found out Blackbeard was going to seek a pardon, he followed. It was clear the life of a pirate wasn’t a match for Bonnet.

While in Bath — then the capital of North Carolina — Bonnet found out England had declared war on Spain. He decided to return to his ship, the Revenge, and become a privateer — a legal pirate paid to attack Spanish shipping. But when he returned to Beaufort Inlet, where his ship was anchored, Blackbeard was gone. All that was left was Bonnet’s empty sloop and 25 members of his crew marooned on a sandbar. Bonnet swore revenge against Blackbeard, and vowed to chase him down.

But Blackbeard had a head start and easily evaded Bonnet, who returned to piracy. He was short on supplies and money, according to his trial transcript.

“They were all running around trying to get a final score before taking a pardon from North Carolina,” Woodard says. “Bonnet may have tried to get one more score.”

But Bonnet wanted to keep his pardon, so he changed his name to Capt. Thomas and renamed the Revenge the Royal James. On July 2, 1718, Bonnet captured the merchant sloop Fortune off the coast of Delaware Bay. He seized the sloop Frances two days later. All three ships sailed into the Cape Fear River that August, where he planned to repair the Royal James.

Unlike his first foray into piracy, Bonnet was the captain this time, according to the transcript of his trial. He earned a reputation for abusing his crew — lashing two men as punishment, and threatening prisoners with marooning if they didn’t work. He was allegedly one of the few pirates to make prisoners walk the plank, but historians have their doubts.

Moore said Bonnet obviously learned things from his time with Blackbeard. “He had to become a little better,” Moore says. “Just from the experience. He was watching one of the best.”

But like Blackbeard, Bonnet was again a wanted man, and South Carolinian pirate hunters were on his trail.

Battle of the Sandbars

News got back to Charleston that a pirate named “Capt. Thomas” was anchored in the Cape Fear River. But South Carolina Gov. Robert Johnson had bigger problems. Pirate Charles Vane, like Blackbeard, attacked Charleston, and Johnson wanted him caught.

Johnson commissioned Col. William Rhett to capture Vane with two Royal Navy sloops, the Henry and the Sea Nymph. Rhett lost Vane, but decided to investigate reports of pirates in the Cape Fear.

Rhett’s flotilla arrived at the mouth of the Cape Fear on the evening of Sept. 26. They spotted Bonnet’s three ships and started toward them when both the Henry and the Sea Nymph ran aground. After scaring the pirate canoes away, Rhett had no choice but to wait for high tide.

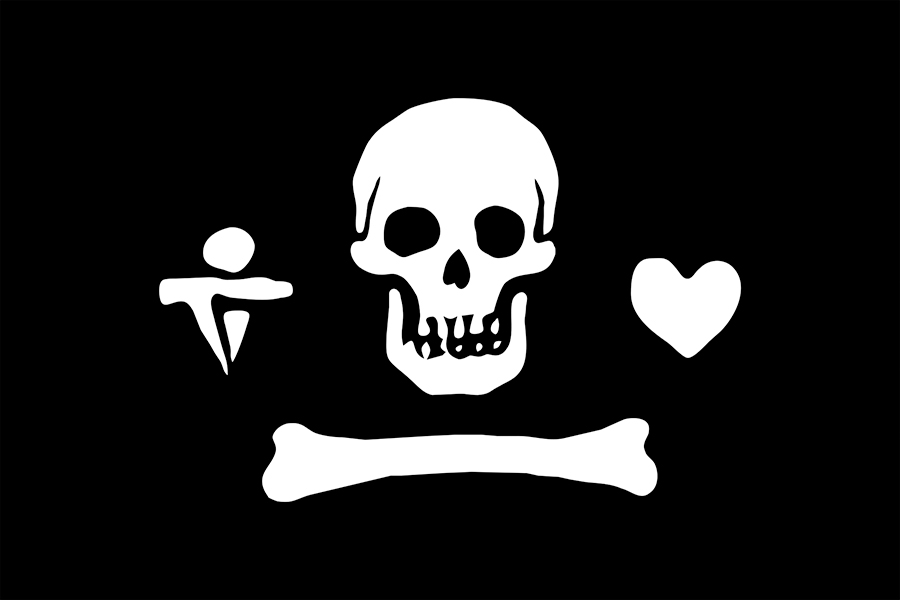

Farther up the river, Bonnet waited for the morning tide. At daybreak, he raised his flag and headed toward Rhett’s ships. As they approached, the pirates fired cannon and muskets.

Rhett got his ships underway and ordered them to bracket the Royal James. As they maneuvered, the Henry and Sea Nymph both ran aground in the unfamiliar river. Bonnet order his crew to hug the river’s western shore to avoid Rhett’s ships, but before they could escape, the Royal James got caught on a sandbar. Only the Royal James and Rhett’s flagship — Henry — were in range of each another.

Both sides unloaded volleys of musket fire. The Royal James’ deck was tilted away from the Henry, giving the pirates a perch to fire upon the British sailors. The Henry’s deck was titled toward the Royal James, leaving the British sailors exposed.

“They kept a brisk fire the whole time,” Rhett reported according to the trial transcript: “The Pirates . . . beckoned with their hats in derision to our people to come on board them; which they only answered with cheerful Huzza’s, and told them it would soon be their turn.”

Bonnet marched along the deck waving his pistols around and threatening to kill anyone who refused to fight. He spotted Thomas Nichols, who had just joined the crew, cowering. Bonnet told Nichols that if he didn’t fight, he’d blow his brains out. As Bonnet leveled his pistol, a nearby pirate was struck, distracting him, Nichols testified at the trial.

The battle raged for five hours until the tide changed. The Henry was freed first. Bonnet could hear the British sailors cheer as they repaired the rigging and closed on the Royal James. Rhett’s second ship, the Sea Nymph, was also freed and sailed toward Bonnet’s vessel.

Vastly outnumbered, Bonnet drew two pistols and ordered his gunner, George Ross, to blow up the ship’s powder magazine. Ross started toward the magazine as Bonnet threatened to shoot any man that tried to stop him. Before Ross could light the magazine, Bonnet was overruled by the remainder of the crew.

A “flag of truce,” according to the trial transcript, was run up the mast, signaling their surrender. Bonnet gave up only after Rhett agreed to negotiate with the governor on his behalf.

Seven pirates lay dead and five were wounded. Ten British sailors were killed and 14 wounded. Rhett stayed in the Cape Fear for a few days to let the wounded recuperate before sailing south. He arrived in Charleston with Bonnet and 34 pirate prisoners on Oct. 3, 1718.

The End

Back in Charleston, Bonnet made one more bid for freedom. He escaped to Sullivan’s Island, but was soon recaptured by Rhett. But the bigger news, according to Woodard, was the mob that tried to free Bonnet and his crew. The trial transcripts describe the mob as almost overthrowing the government.

“That suggests Stede Bonnet had some significant rank and file following among the pirates or rank and file supporting pirates,” Woodard says.

The support likely came from the fact that Charleston was an economic hub, Woodard says. Goods fenced in the Caribbean often made their way to the city.

“There could be quite a few people with economic, political affiliations with Stede Bonnet,” Woodard says.

On Nov. 10, 1718, Bonnet stood trial for two counts of piracy. He defended himself using his high-born background and his time as Blackbeard’s prisoner as a defense. But like his pirate career, the trial ended in failure. Bonnet was sentenced to death and hanged a month later at White Point in Charleston. He was executed a few weeks after Blackbeard was killed by the British Royal Navy on the inlet side of Ocracoke Island.

The death of Blackbeard and Stede Bonnet ushered in the end of piracy’s golden age. But their lives represent more than just thieves on the water. Woodard argues in his book piracy was a political protest and the first seeds of democracy. Pirate ships weren’t run with the captain as God like the Royal Navy or the merchant fleet. Crews voted for their leader, and loot was divided among the crew.

“It shows while they were stealing and breaking the law, that is not really what was going on,” Woodard says. “It would be one thing if only the pirates saw themselves in this light, but tons of people took the pirates’ point of view. They were Robin Hood’s men fighting the good fight against the autocratic transatlantic empires. You had a democratic movement a good 70 years before.”

But how does Bonnet fit into that narrative? He was part of the transatlantic system, raised in the upper class of one of Britain’s richest colonies. That isn’t the portrait of a revolutionary fighting for the common man. He was a one-percenter. His early pirate days are more like a rich guy playing the rebel by dying his hair, buying a leather jacket and riding a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. It was only when he was left with nothing, duped by Blackbeard, that Bonnet finally became a pirate.

Not a good pirate, but a gentlemen pirate.

Kevin Maurer is an award-winning journalist and best selling co-author of No Easy Day, a firsthand account of the raid to kill Osama bin Laden. His next book, American Radical, will be out in October.