Hidden in the Port City’s urban nooks and crannies are creative makers galore. They take to wood or wire. High-end or high-tech. They shape ships or sounds. Like soothsayers, they hold material in hand and conjure. Each maker is committed to process and a product: Inventing, assessing, refining pushes their craft, their creation, into being.

As the Wood Turns

The artist who makes mushrooms out of twigs

By Mark Holmberg • Photograph by Andrew Sherman

There’s a treelike spirit of calm and steadiness that radiates from 73-year-old Jean LeGwin, especially when she’s turning a piece of wood and the chips mist around her.

“Totally zen,” she says. “Time falls away.”

Finding her and her work is like a soothing and surprising gift at the end of a quiet little road near Ogden Elementary School. There, on a sweet spit of land overlooking Page Creek, sits her unique aluminum, steel and wood trio of buildings — home, shop and shed — designed by Wilmington architect Michael Kersting.

It’s a place that inspires. And LeGwin is totally inspired. Her 28 years of woodturning have only honed her passion for all of its possibilities.

“There are so many things you can do with woodturning,” she says. “Objects you’d never guess were turned.”

And here’s where this story turns: This shy, gentle, zen-like woman is an absolute woodturning brawler — pushing the envelope, going smaller, thinner, deeper, more difficult — “playing with forms,” as she puts it.

Look at her tiny, copper-detailed box turned out of one piece of wood. No way! Or a bowl so thin you could use it for a lampshade. How did that not shatter while turning or sanding? And how could a human hollow out a bark-infused ball of oak and make the walls that thin, all through a pinkie-sized hole in the top?

“I like challenge,” she says.

First, she pictures a finished piece. “How do you get there? What are the problems? Every step brings a new set of problems. How do you solve them?”

Her passion began in childhood, when she loved to whittle. (When was the last time you saw someone do that?) “I was fortunate to have a father who was always working with wood,” LeGwin says.

In Boston, where she owned a design and layout firm in the high-stress world of publishing, she took a woodworking class to unwind. “I got totally hooked.”

When she retired and sold her business after 35 years, she came to the family land on Pages Creek and built her home and shop and joined the Wilmington Area Woodturners Association. Her shop is a woodworkers dream, anchored by her beloved Stubby lathe from Australia.

This is a woman who knows and loves wood. Her favorite? “I try to get free wood,” she said with a smile. Cherry is cherished by her. But she has and loves a little bit of everything from around world, even random shipping dunnage and exotic seed pods from Africa. What she doesn’t like is wasted wood. “Even twigs,” she says. “I make little mushrooms out of them.”

That’s how her world turns.

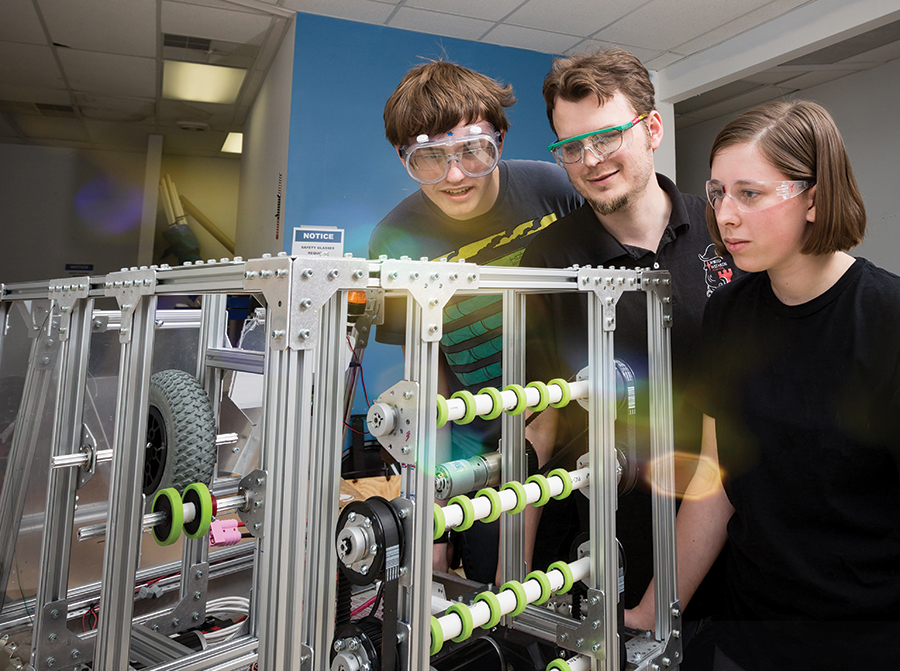

Wired Wizards

A high school robotics team aims high

By Christine Hennessey • Photograph by Mark Steelman

What if you had six weeks to build and program an industrial-size robot? What if that robot had to play a complex field game against other robots? Your team would have strict rules, limited resources and money to raise. And you’d still have to go to high school. If you were a Wired Wizard, you’d take on the challenge. Not only that — you’d accomplish it, too.

The Wired Wizards are a team of 25 students from high schools across New Hanover County who build and program robots. Founded in 2012 and supported by Port City Robotics, a local organization that fosters STEM opportunities for area youth, the Wired Wizards are split into three major components. The Build team is responsible for building the robot, which includes construction and electrical wiring. The Programming team writes the software that enables the robot to play the game. Finally, the Business Development team is responsible for marketing, fundraising, event planning and community outreach.

Their ultimate goal? Competing in the FIRST Robotics Challenge, an international competition that combines the excitement of a sporting event with the challenges of science. Last year the Wired Wizards won North Carolina’s State Engineering Inspiration Award and were one of 900 teams to qualify for and travel to the World Championships in St. Louis. This year, they hope to go even further.

Benjamin Barbour, president of Port City Robotics, has an additional goal for the group. He’s taking the long view. He wants the team to put southeastern North Carolina on the map for robotics and other tech fields. When businesses are looking for employees who are ready to tackle the latest technological challenges, he hopes they look here first. And the wizards will be ready.

So far, his plan seems to be working. The majority of Wired Wizards have gone on to college in STEM-related fields or confirmed their passion for communications, marketing and business. By working hard and working together, they’ve prepared themselves for a bright and successful future, all the while having fun, building robots, and leading the next generation of Wilmington’s tech community.

Learn more at www.wiredwizards.org

The Guru of Tone

Guitar notes like a seraphic choir

By John Wolfe • Photograph by Mark Steelman

Move over Menlo Park. Michael Swart is the Wizard of Carolina Place.

Swart, founder of the Swart Amplifier Company, builds guitar amps that produce a feeling of directness. There is as little electrical interference as possible between what the musician plays and what the audience hears – a feat that takes quite a lot of engineering. He’s become quite famous for his amps, not surprisingly, garnering devotees like Joey Santiago of The Pixies and The Martinis, Jeff Tweedy of Wilco, one of the guys from They Might Be Giants, and even the Crown Prince of Jam himself, Trey Anastasio of Phish phame.

In his Wrightsville Avenue workshop, Swart is surrounded by vintage machines, machines from a time when things were built to last or at least, to be tinkered with: a VW bug, BSA motorcycles, a VéloSoleX French moped. He prefers the ’50s and ’60s. “Each thing almost talks to me, gives me a story,” he says.

The story of how Swart went from musician and tinker man to boutique amp guru begins at the Starway Flea Market. “I bought an old Supro for like 40 bucks,” and he got to work. With help from a woodworker uncle (to build the boxes), a Web-savvy college friend and Swart designing amps from vintage technology, a career was launched. “Every time we put an amp up on eBay, it sold. I think we sold five or six amps the first year, and then I started developing an amp that had reverb and tremolo — that’s what I always wanted to do.”

The result was the Space Tone Reverb, the signature guitar effect of Swart.

“Here,” he says, gesturing to what could have been a prop from a schlocky sci-fi movie: a plywood plank with exposed circuitry and several shrunken lightbulbs, which turn out to be tubes. “This is what I’ve been working on,” he says. He flips a switch to warm up the device, which he tells me is a new kind of push-pull amplifier. “It’s still a prototype; I haven’t released it yet.” The tubes glow a soft orange. He smiles. “I grew up with an old Silvertone stereo in the house. I would turn it on and peek in the back to watch the tubes glow. It’s like looking at space. You can actually see electrons flying from this plate to that plate.”

He plugs in his red guitar, switches the amplifier on, and begins to play. Chords cascade sweetly from the speaker. The tone is grand and full, filling the room with an aching sonic beauty, the notes like a seraphic choir. Subtle thoughts — electric pulses firing between the neurons in the brains — tumble out joyfully into the big world of vibrating molecules. Swart twirls a dial, strums the strings, reverberating sound upward through the roof into the stratosphere high above Wilmington.

www.swartamps.com

Hand to Wood

Where wood is manifested into boats

By John Wolfe • Photograph by Andrew Sherman

Mark Bayne, the lead instructor of the school of wooden boat building, is a lion-built man with a mane of graying hair swept back. He speaks with efficiency because he’s got work to do. His shop will produce three new boats this year. A career boat builder, he graduated from Cape Fear Community College’s inaugural boat building class in 1979 and boomeranged back to run the program.

Like all good workshops, Bayne’s is loud and well-lit and redolent of sawdust. Inside are big saws and drill presses, stationary planers and vacuum hoses. Outside, on the bank of the river, rest sleek sailing dinghies, elegant and fragile as upturned shells of walnuts; stout little work skiffs, heavy with the promise of fish.

Boat design takes its first step inside, in the “loft.” Lofting, as Mark explains it, is life-sized marine drafting. The floor is white and gridded, overlaid with full-sized organic curves from which classic boats are crafted, scaled up in pencil from smaller plans. The next step: Manifest these shapes in wood.

On the shop floor below, two students work. Kent Harrell, retired engineer, grew up (“at least, I attempted to,”) in eastern North Carolina, and learned to water-ski behind a Simmons Sea Skiff. He’s wanted one ever since. After 20 years of waiting, he’s finally building his boat. At the moment it’s a stack of lumber on the floor, a model on a table, a dream in his mind.

Zach Medeiros, a young man with a black beard and perpetual half-smile, doesn’t know of a single boat built exactly to its plans. “There’s always changes along the way,” he says. For instance, when they built the Simmons model and flipped it over, they realized the stringers made an inaccessible place where water could collect and rot the hull. So they’re nixing the stringers and using plywood instead.

Outside, beside the MARTECH catamaran, floats a 24-foot-long Harkers Island-style white skiff. She has varnished wooden ribs and lots of flair in the bow, which gives her a dry ride and that classic Carolina styling. She’s fast, too: Mark has clocked her at 40 mph. “(Last year) the school needed to replace a similar boat (used in boat handling and marine sampling classes),” Mark says, “so I built them this one.” No plans and only minor lofting. He had an image in his head, shaped from a lifetime of boat building, and just built it. The students who helped got to see a straight transfer: from thought to hand to wood. The process looks a little bit like slow-motion magic, conjuring fantasy and converting it, through hours of careful labor, into something seaworthy.

Learn more at cfcc.edu/martech/boat-building-school

The CFCC Riverfront Boat Show is April 1, 9:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m. on the Cape Fear River at Walnut Street.

Grain of Perfection

In a shop that’s more like a museum, furniture artist Robert Hause brings old treasures back to life

By Mark Holmberg • Photograph by Andrew Sherman

Robert Hause has been surfing the shimmering waves of Wrightsville Beach since he was a kid. But it’s the shimmering rays of oak grain and the mysteries of fine woodworking that truly consume him.

“See the way they radiate?” he says, caressing a fully dressed plank of quarter-sawn oak in his Wrightsville Avenue shop — museum is more like it — filled with original fine furniture from the Arts and Crafts era (1895–1920) as well as the precise reproductions for which he is famed.

This 59-year-old woodworker is absolutely infatuated. He knows every drawing, photo and word in the historic catalogs that litter his place. He knows the serial numbers, dimensions, the quirks and flaws and most important the makers’ secrets of the legendary desks, chairs, dressers, tables, hutches, hall trees from masters such as Gustav Stickley, Rennie McIntosh and Charles Rohlfs.

His Dutch/German shepherd companion is named after the legendary Arts and Crafts metalsmith Dirk Van Erp.

Hause can’t trace how or why his fascination started. It’s almost as if it was written on his soul at birth. As a youngster, “instead of studying books I was pulling out drawers and looking at dovetails,” he says.

The Hoggard graduate would go on to earn a geology degree at UNCW and work a 20-year operations career at the Brunswick nuclear power plant. But woodworking was ever his passion, he said. “I’ve always had a shop.”

His current space is a bit more cramped. “It’s a small shop,” he says, “a one-man, one-dog show.”

But what a show. There’s a small fortune in precision saws, sanders, drills, routers and hand tools that fill his sawdusted shop. The house in front testifies to his relentless search around the world to find the best, trickiest and rarest examples from the Arts and Crafts era and then repair or refresh them or build copies practically indistinguishable from the originals. It’s a perfect match.

Antiques Roadshow would likely love to have his encyclopedic knowledge. But his understanding is more intimate. He has taken these pieces apart, seen exactly how they were made, how they evolved to address weak points, probably even what the makers were thinking as they designed them.

It is a never-ending quest for perfection.

Smell his cocktail of vinegar and steel wool that darkens his creations that need it. There’s his clear tent for aging his furniture with ammonia fumes. “I have my own recipe for shellac,” he says.

But don’t get the idea that he’s just an imitator whose pieces sell around the country. Hause just finished a fabulously elaborate original grand hutch that took nearly six months of full-time attention. But it’s not really work, he says, “It’s just the love of it.”

Learn more at www.artofthecraft.com

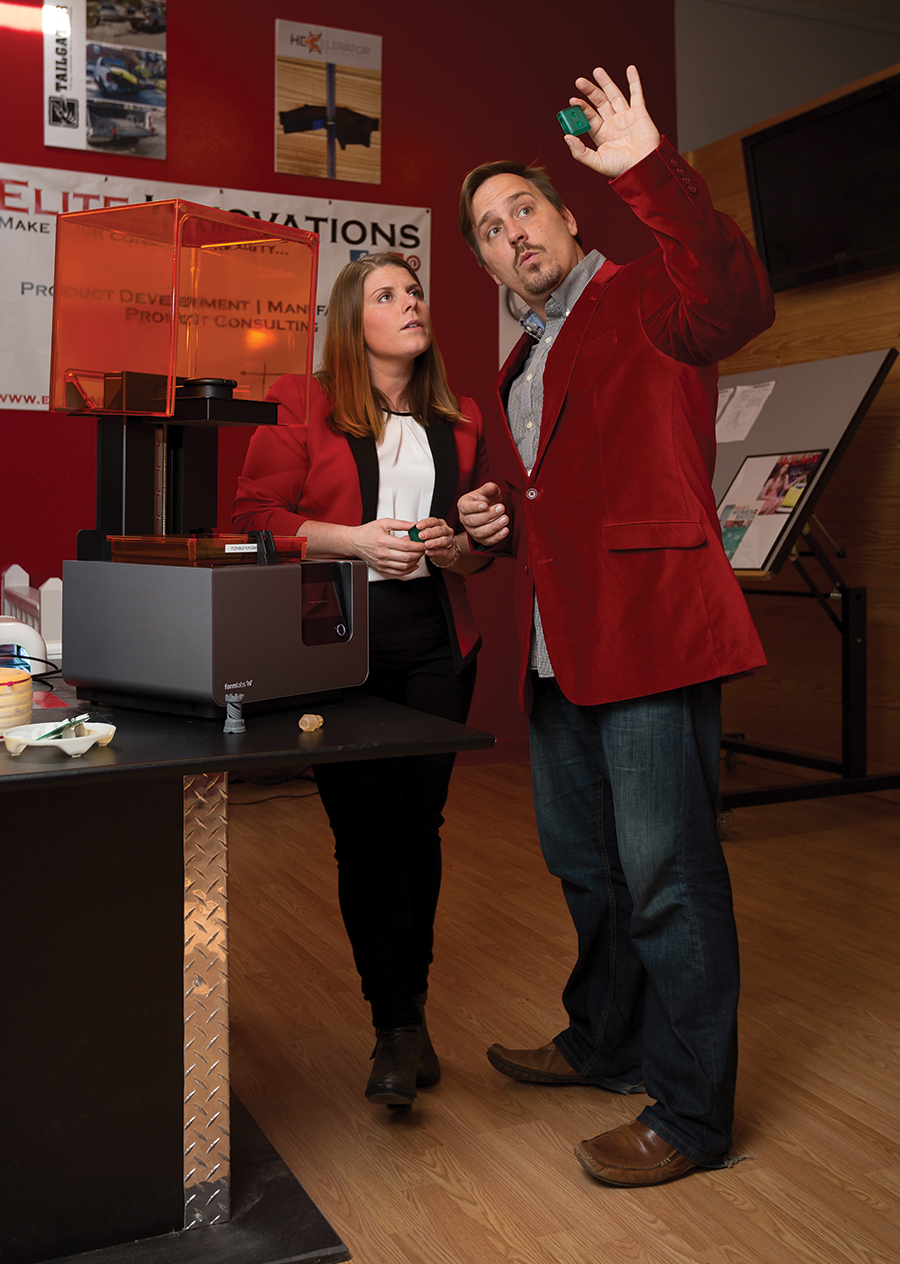

Space for Innovation

Elite Innovations is a firm designed to help

By Christine Hennessey • Photograph by Mark Steelman

Thomas Edison said, “To invent, you need a good imagination and a pile of junk.” While the team at Elite Innovations, a product development company, wouldn’t describe their 3D printers, CAD software and industrial designers as “a pile of junk,” they nevertheless embrace this spirit.

Founded in 2013 as a Makerspace, Andrew Williams and Ed Hall provided a large workshop for Wilmington’s inventors to turn their ideas into physical products, such as TailGator, an innovative truck bed extender, affordable dentures that can be fitted at home, and ORIGOConnect, a “distraction management system” that works with a driver’s smartphone while his or her vehicle is in motion and sends important information to a monitor.

As Elite Innovations helped people design and build, they soon realized their clients needed more assistance in the development stage — more imagination, less “junk,” if you will. And so, like all good inventors, they adapted.

They hired an industrial designer, a sales rep and two programmers. They also started a robust internship program, taking on talented students from UNCW, Cape Fear Community College, NC State, and Virginia Tech. With the new team in place, they were ready to work — in a downtown office, not a warehouse.

Williams says in a perfect world, clients come to Elite Innovations when they’re still at the starry-eyed idea stage. This makes it easier to guide a project, enhancing and adjusting their clients’ vision with the market in mind. (But if a product already exists, the team still seeks to find ways to add value or innovate.) They go through multiple iterations to ensure the final design is as close to perfect as possible, then focus groups allow them to zero in on blind spots.

Once the design is finalized, then comes the making; the team builds prototypes, helps source manufacturing resources and marketing opportunities. By the end of the process, the inventor has something better than a brilliant idea. He or she has a product.

Learn more at eliteinnovationsllc.com