By Chris E. Fonvielle Jr.

Hope springs eternal! The old adage was on the minds of members of the Public Archaeology Corps when they met with city officials and a representative of a real estate development company at Wilmington’s City Hall in the summer of 2017. They hoped to receive permission to search for a famous lost landmark — the Rock Spring — in the vicinity of Chestnut and Water streets in city’s historic district. But time was of the essence, as a construction project was slated to soon begin on the site.

In an ambitious public-private venture, the city of Wilmington and a real estate developer planned to build a high-end, mixed-use project called River Place, stretching from Chestnut Street north to Grace Street and eastward from Water Street halfway up the block toward Front Street. But first things first. A massive concrete parking deck, erected in 1968, would have to be demolished, and then holes dug deep below ground for footings to support the complex of buildings, including one imposing 12-story structure.

Underneath the property, however, lay the remains of almost three centuries of Wilmington history — the foundations of old homes and businesses, as well as artifacts. Below the levels of historical material culture dating back to the city’s earliest days would be Native American artifacts many hundreds, or even thousands, of years old.

Among the potentially significant archaeological features on the site was the Rock Spring, whose waters, according to local legend, were so pure and sweet that anyone who drank from the spring would be compelled to return to Wilmington, if not make it their home. The Public Archaeology Corps was hopeful of finding the Rock Spring if city officials and the developer agreed to allow a search.

The main mission of the Public Archaeology Corps (PAC) — a Rocky Point, North Carolina–based nonprofit group consisting of archaeologists, historians and volunteers — is to mitigate the loss of archaeological sites on privately owned property as a result of development, in large part by building relationships with owners of land that contain archaeological sites. Educating the public about local history and archaeology is also a crucial component to the Corps’ objective. “We do (archaeology) in such a way that people can come in and see what we’re doing, ask questions, see the whole process of archaeology done,” explains Jon Schleier, founder and director of the PAC, in a Wilmington Star News interview. “We’re really trying to bring it home to people, to the average person, that archaeology is very much a thing here in southeastern North Carolina.”

After a constructive meeting, city leaders and the developer’s agent gave the PAC two days to find and document the Rock Spring. After years of planning, authorities were eager to get construction underway, and that was all the time they could spare. Although the archaeologists would have preferred more time to do their work, 48 hours was better than nothing. The search was on!

Wilmington is a beautiful old city rich in history. It began as a trading center on the east side of the Northeast Cape Fear River near its confluence with the Cape Fear River, and 28 miles from where the waterway empties directly into the Atlantic Ocean. In 1733, a group of developers laid out a town they called New Liverpool, but renamed Newton the following year. Although slow-going at first, Newton’s growth flourished when Gabriel Johnston became royal governor in 1734. During his long reign, he used his political powers to transform the town into a place of considerable importance, and actively promoted its settlement and development. In 1739, North Carolina’s General Assembly passed an Act of Incorporation for the Town of Wilmington, naming it in honor of Gov. Johnston’s patron, Spencer Compton, earl of Wilmington and lord president of His Majesty’s Council under King George II.

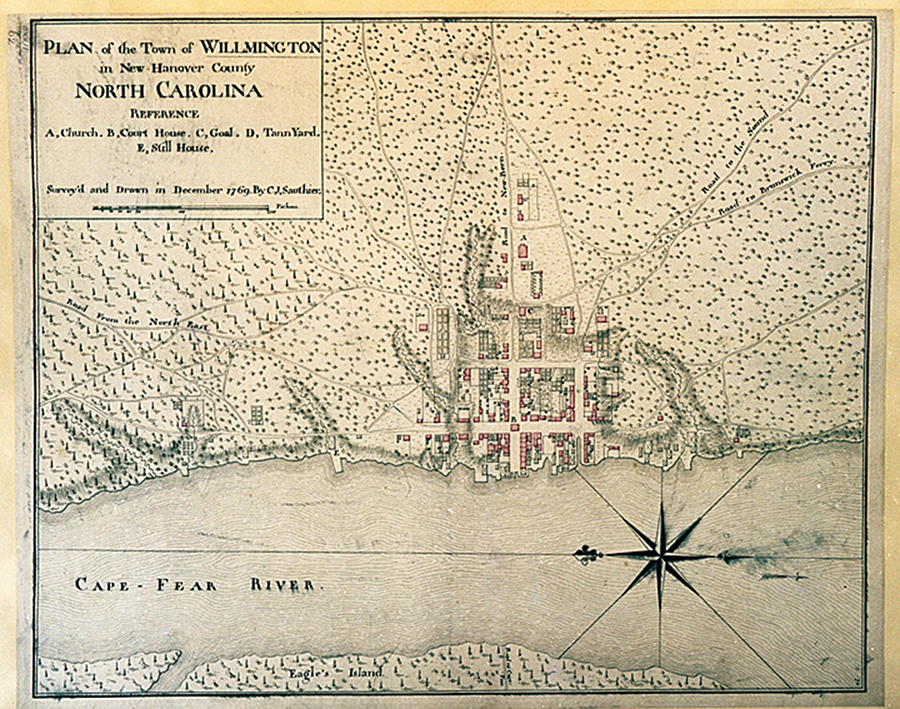

An official map of Wilmington, produced by royal cartographer C.J. Sauthier in 1769, reveals a relatively small town with houses, stores and a public market and courthouse clustered around Market, Dock, Princess and Second streets. Fewer than 1,000 people lived in Wilmington at the time. The map also depicts eight creeks, seven of which made their way to the Cape Fear River to the west. The names of four of them are known: Jacob’s Run, Willow Spring Branch, Tan Yard Branch and Jordan. Jacob’s Run emanated at what is today the southwest corner of Fourth and Princess streets, and ran southwesterly to the river at the foot of Dock Street. Tan Yard Branch, named for a leather tanning yard along its banks, and Jordan, “a stream of some two to five feet deep,” were located north of town.

Natural springs at the headwaters of the creeks were sources of water for Wilmington’s early residents. The streams themselves, however, became impediments to the town’s development. Town officials ordered that owners of lots with streams keep them clear to prevent any overflow from heavy rains. They also had Jacob’s Run, which ran through the middle of town, covered by a brick structure to enable people to cross it more easily and to build atop. In the process they created a system of tunnels underneath streets, buildings and yards that subsequently generated legends and stories about smugglers, pirates and fugitive slaves over the years. Eventually all of the remaining creeks in the downtown area were bricked over or filled in.

As for drinking water, the Cape Fear River was dark, muddy and a little salty when the tide flowed upstream. Many residents dug wells and cisterns in their yards and gardens, or filled buckets and casks at springs and ponds around the town. One spring was located at the foot of modern-day Harnett Street. Wilmingtonian Henry Nutt recalled that, between 1815 and 1822, he and a group of friends, known as the Arabs, used to roam, explore and play north of Jordan in a wooded area popularly known as Paradise. A huge outcropping of rock poked toward the Cape Fear River, he remembered, on the west side of which “issued a fountain of the purest water which had formed a kind of basin or spring partially covered by the overhanging, shelving part of the rock.”

Yet the spring, generally referred to as Paradise Spring, was situated too far from Wilmington’s main residential and commercial district for people to walk out and then lug back heavy, water-laden buckets. In the late 1830s, Paradise was lost to the construction of wharves, a steam mill, turpentine distillery, and the Wilmington and Raleigh Railroad (later renamed the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad). “And such is life” in the name of progress, Henry Nutt lamented.

The most popular spot for drinking water became the Rock Spring on Chestnut Street, just east of the intersection with Water Street. Sometime before 1817, engineers built Water Street to connect the docks, wharves, warehouses, and commission merchant houses that cropped up as Wilmington grew into the state’s most populated urban center and busiest seaport.

As early as the 1820s, the Rock Spring “was universally used by the inhabitants; in fact, it was the spring of the city,” wrote “An Old Citizen” to the editor of the Wilmington Daily Review in 1879. “Its great flow was not only sufficient to supply all the citizens in its vicinity, but every vessel that came in port supplied their water casks for the outgoing voyage.” The earliest extant public record of the Rock Spring comes from the minutes of town aldermen meetings in 1823. On Sept. 3, commissioners instructed James Usher to “remove the naval stores or any other article which he may have lying on Chestnut Street near the Rock Spring, within one week from the date hereof,” under penalty of a heavy fine.

By about 1830, the Rock Spring had become so famous that businessmen promoted their establishments as being located nearby and, in some cases, named them in tribute to it. Merchant R.W. Brown advertised barrels of “Rock Spring brand” gin for sale. In 1839, James Petteway established a livery stable on the north side of Chestnut Street “near the Rock Spring.” In the autumn of 1846, J.D. Love advertised New York and Boston manufactured furniture and household items imported to Wilmington for sale at his Rock Spring Furniture Warehouse. Four years later he expanded operations by employing “experienced and skillful workmen” to custom- make and repair “all articles of cabinet furniture,” renaming his business the Rock Spring Furniture Manufactory and Ware-Rooms.

The week before Christmas of 1846, David Thally opened the Rock Spring Restaurant for the “accommodation of the public,” proclaiming “The Old Rock Spring Forever!” in his print advertisements. He offered “Refreshments at all hours of the day and night.” In the late 1840s, Alfred Alderman opened the Rock Spring Hotel on the south side of Chestnut Street, halfway up the block between Water and Front streets. In 1858, Mary S. McCaleb had become the “Proprietress” of the Rock Spring Hotel, claiming that “her rooms (were) kept in the best possible manner, rendering every comfort and convenience to her guests in her power.” In the spring of 1860, Edward B. Dudley, son and namesake of the former president of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad and governor of North Carolina, opened the Rock Spring Ice House on North Water Street.

But when did the legend about the mystical powers of the Rock Spring’s waters begin? An anonymous author, known only as “C,” penned an epic poem in March 1850, titled “The Rock Spring Water,” for the Wilmington Chronicle. “There is a legend that he who drinks of the ‘Rock Spring,’ must henceforth become a resident of (Wilmington).”

“Who drinks the Rock Spring wave below

Can never leave this shore.

But thou shalt stay and dwell with me

For now thou cans’t not roam.”

Writing to the editor of the Wilmington Sun in late March 1879, “Phoenix” claimed that, when he was a boy half a century earlier, “the same tradition that attaches to the old Rock Spring, at the foot of Chestnut Street, was as common as it is to-day.”

The Wilmington Star reported in 1872 that Col. J.R. Purcell had returned to Wilmington to resume control of a hotel called the Purcell House. “The colonel has evidently partaken of the famed ‘Rock Spring water,’” noted the editor, of which it is said that “when a person has once indulged himself or herself with a drink, they can never remain permanently away from Wilmington.” The newspaper ran a notice the following year that James McCormick, a “well known merchant tailor, and formerly a citizen of this city, has come to live with us again. He must have drunk ‘Rock Spring water’ before he departed.” Charles I. Kline moved to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1898, but returned home to Wilmington within a matter of months. “Rock Spring water did it!” claimed the Wilmington Dispatch. Friends of Mary Hinsdale Slocumb of Fayetteville induced her to “imbibe freely of Rock Spring water when she left the ‘City By the Sea’ in 1906, knowing that she would be “compelled by its magic charm to return.”

By the turn of the 20th century, drinking the waters of the Rock Spring had become a dangerous proposition. Both residential and industrial development in downtown Wilmington had severely contaminated the ground water. In early January 1900, the chamber of commerce publicly displayed quarts of water taken from wells throughout the city, and from the Rock Spring. Every sample contained high amounts of organic matter. Finally, in 1907, Dr. Charles T. Harper, superintendent of health, warned citizens about the Rock Spring’s contamination, reporting that “the water is polluted and is not fit for drinking purposes.” The spring fell into disuse, and was soon covered by more urban development, most notably a large parking deck built in 1968.

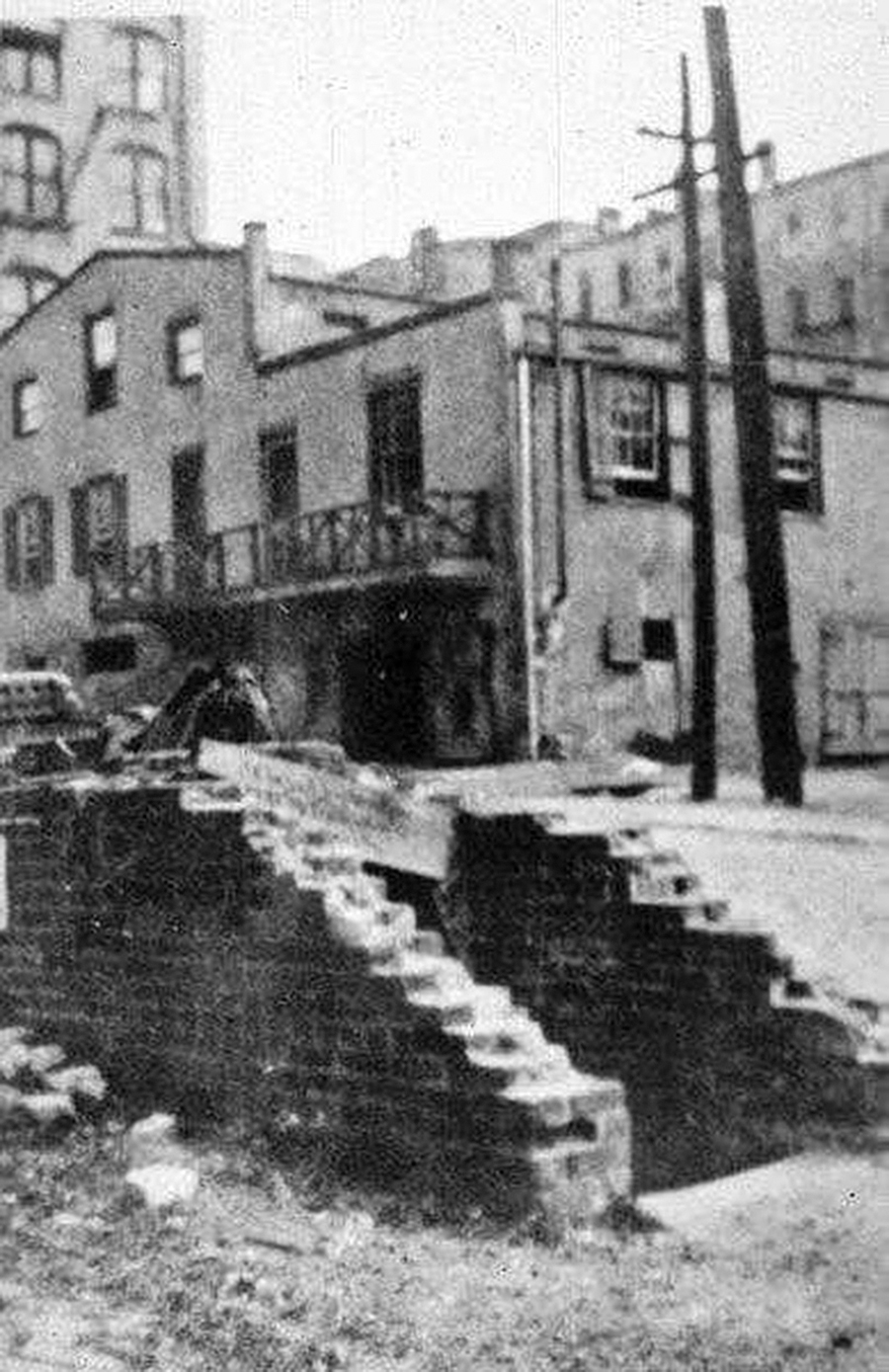

Rediscovering the Rock Spring, if it even still existed, posed quite a challenge to the PAC, especially considering the time constraints it faced. To pinpoint its location, the group relied on several sketch maps drawn by Nicholas Shenck that accompanied his journal of Wilmington in the days before the Civil War; one extant photograph of the Rock Spring, with the Rock Spring Hotel in the background, taken by Andrew Howell probably before 1913; and a physical description of the spring by Henry Bacon McCoy from his 1957 book, Wilmington: Do You Remember When?

McCoy described the Rock Spring as being near the foot of Chestnut Street, just off the sidewalk on the north side. A 12-inch brick wall, built before 1870, enclosed the spring on three sides, and a brick arch covered it. The entrance end was open toward the river, and well-worn slate steps led downward approximately eight feet below the level of the street. At the bottom a spring of clear, cool water bubbled up through the sand. The overflow was carried to the river through a terra-cotta pipe. A gourd with a long handle “for ready use” hung on a spike hammered into the brick wall. What McCoy could not answer, nor has anyone, is why it was called the “Rock Spring.” Perhaps it had something to do with the large number of ballast stones unloaded from the cargo holds of ships that had docked along Wilmington’s wharves in the 1700s and into the 1800s.

Using a heavy piece of construction equipment called a hydraulic excavator and long-handled shovels, PAC volunteers dug for about five hours on Dec. 17, 2017, before they finally hit pay dirt. They found the Rock Spring, or rather the remains of the three brick walls that surrounded it. Over the following two days, diggers excavated to the bottom of the shaft, but found no evidence of the spring itself. They did, however, uncover the top slate step and pieces of others mentioned in McCoy’s account of the Rock Spring, and some artifacts, including a small medicine bottle, ceramic shards, and iron nails that were probably thrown into the spring after it had been abandoned. They also found a sewer pipe, likely laid in the 1930s or 1940s, that cut through the back wall, but most of the structure had survived. Archaeologists made detailed line drawings and took photographs of the key features for posterity, knowing that the spring site would be destroyed with the construction of River Place. Hopefully the developers will incorporate the flagstones into one of their buildings and erect a historical plaque commemorating one Wilmington’s most famous landmarks and the legendary story of the magical powers of the Rock Spring’s waters.

The author wishes to thank Joe Sheppard in the North Carolina Room at the New Hanover County Public Library, and Daniel Norris of SlapDash Publishing for their assistance with this article.

Chris Fonvielle is a professor emeritus in the Department of History at UNC Wilmington, and a recent recipient of the Order of the Long Leaf Pine for distinguished service to the State of North Carolina. He is also the author of books and articles on the history of Wilmington and the Lower Cape Fear, where he was born and raised.