The Voice of Black Mecca

In the fall of 1898, when an angry white mob burned The Daily Record, the black community of Wilmington lost its most important voice in editor Alex Manly

By Kevin Maurer

It was dark when Alex Manly approached a bridge on the outskirts of Wilmington in the fall of 1898. Up ahead, a group of Red Shirt guards waited.

The white men — dressed in red tunics and carrying Winchester rifles — ordered him to stop. Alex Manly and his brother, Frank — newspaper editors and publishers — were wanted men, declared outlaws to be killed on sight by the white supremacist terror squads intimidating non-Democratic Party voters on the eve of the 1898 election.

The Red Shirts planned to lynch Manly, the editor of The Daily Record, the city’s predominant black newspaper. He was a vocal opponent of the mob’s attempts to paint the black community as rapists, criminals and interlopers.

Hours earlier, a white friend — rumored to be three men but whose true identity is lost to history — gave Manly $25 and the password needed to pass the checkpoint.

“May God be with you, my boy,” the white man told Manly according to a letter written by Manly’s wife in 1954. “You are too fine to be swung up to a tree.”

Manly slowed the buggy as he approached the guards and gave them the password. It was dark, and Manly could pass as white. The guard — mistaking Manly for a white man — asked why he was leaving.

“We’re having a necktie party in Wilmington, where are you going?” the guard asked.

“I am going after that scoundrel Manly,” Alex Manly said.

The guards approved and loaded his buggy with Winchester rifles. They stood aside as he escaped over the bridge.

A few days later, a mob led by the Red Shirts and Alfred Moore Waddell, a former Confederate officer, marched from the armory on Market Street east to Seventh Street and burned the Daily Record offices. It was the opening battle in America’s first and only coup. And like any war, victory can’t be won with only guns. It must be sealed by a greater truth.

Manly stood in defiance of the mob’s truth. So, he had to go.

“He was the only one to stand up against it,” says David Zucchino, the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter and author of Better Get a Gun, a retelling of the 1898 coup coming out next year. “This wasn’t a riot. It was planned. It was an uprising and a white revolution.”

Housepainter to Editor

Manly was born in 1866 near Raleigh. He was a descendant of Charles Manly and his slave Corinne Manly. Manly went to Hampton University, a black college in Virginia, before coming to Wilmington, first as a housepainter and then a newspaper editor.

It was during this time that he met his future wife, Caroline Sadgwar Manly. She was headed downtown to shop with her mother when she passed her father’s worksite, according to a 1953 letter Caroline Sadgwar Manly wrote to her sons. She smiled at her father as she passed, but Manly thought she was smiling at him.

“I saw him but did not notice him, as I thought sure he was a white man and no nice girl in those days would think of smiling at any man she did not know and a white man was out of the question,” Caroline Sadgwar Manly wrote.

Alex Manly told Caroline Sadgwar Manly’s father he wanted to meet her.

“If you prove yourself worthy you may meet her someday, but you had better get to painting that cornice up there, instead of gazing at every little petticoat going down the street,” he said, according to the letter.

Months later, Alex Manly and Caroline Sadgwar Manly became friends just before she went off to Fisk University. An accomplished singer, Caroline Sadgwar Manly also learned to set type on the Fisk Herald, the school’s newsletter. When she got back to Wilmington, Manly and his brother were running The Daily Record. She started working in the Daily Record offices.

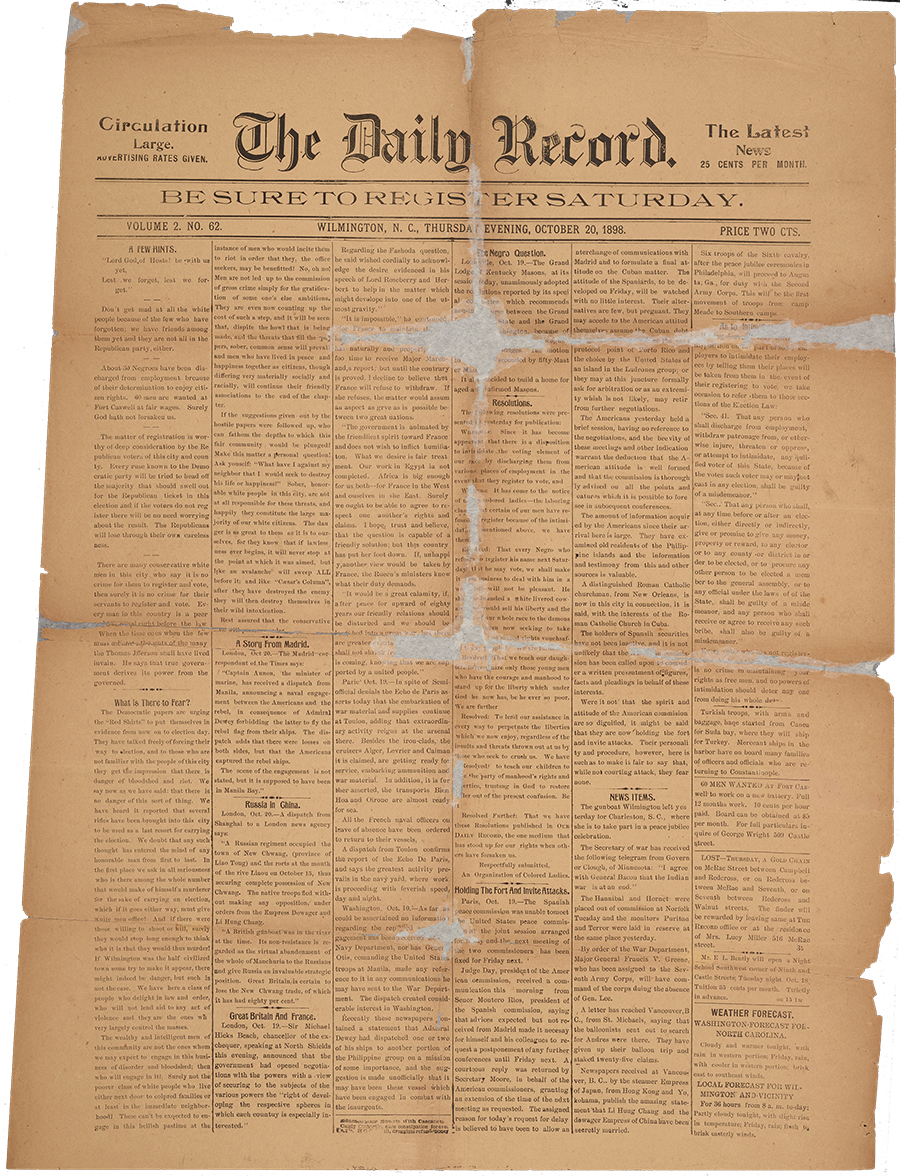

Alex Manly started The Daily Record with his brother, Frank, in 1895, advertised as the “only Negro daily in the world.” It was published from an office at the corner of Seventh and Nun Streets. Three years after buying the paper, the brothers expanded from a weekly to a daily. The paper had white advertisers and a broad subscription base. But at its core, it was the voice of the black community in Wilmington.

“He was an advocate of fair treatment,” says Zucchino. “He demanded better treatment of blacks in the colored ward of the hospital. He focused on better roads in black neighborhoods.”

UNCW professor Philip Gerard, author of Cape Fear Rising, about the 1898 coup, described Manly as a moderate, temperate man. “His real glory was unglamorous community reporting,” says Gerrard. “He was the glue that held the community together. He was exactly the kind of leader middle class Wilmington needed.”

Wilmington was unique among Southern cities. It was one of the most integrated places in North Carolina. In 1898, the black community made up 55 percent of Wilmington’s population. But the black community’s real power was economic. Blacks accounted for 30 percent of Wilmington’s craftsmen. Carpenters. Builders. Jewelers. Painters. Blacksmiths. The community was also moving into more prominent businesses, like The Daily Record. There were six black lawyers, an architect, and three of the city’s aldermen were black.

Wilmington was nicknamed “Black Mecca.”

But trouble was brewing during the 1898 midterm elections.

Ballot or Bullet

Wilmington, like much of North Carolina, was run by a coalition of black Republicans and white Populists. This fusion coalition had won every statewide office the last two elections on a platform of self-governance, free public education and equal voting rights. The Democrats needed a campaign theme for the 1898 midterm elections.

They picked race.

“North Carolina is a WHITE MAN’S STATE and WHITE MEN will rule it, and they will crush the party of Negro domination beneath a majority so overwhelming that no other party will ever dare to attempt to establish Negro rule here,” Furnifold Simmons, the Democratic State party chairman, said.

Newspapers like The News & Observer of Raleigh, The Charlotte Observer and the Wilmington Morning Star, founded by former Confederate Maj. William H. Bernard, were recruited to push the agenda through hateful editorial cartoons portraying the state’s black population as animals and rapists. A common theme was black men attacking white women.

Rebecca Felton, a women’s suffragist, called for the lynching of black men to protect white women in a speech to the Agricultural Society at Tybee Island in Georgia. “When there is not enough religion in the pulpit to organize a crusade against sin; nor justice in the court house to promptly punish crime; nor manhood enough in the nation to put a sheltering arm about innocence and virtue — if it needs lynching to protect woman’s dearest possession from the ravening human beasts – then I say lynch, a thousand times a week if necessary,” Felton said.

Her speech was reprinted in Wilmington. “It got under his skin so to speak,” Caroline Sadgwar Manly wrote in a 1953 letter. Manly responded in an August 1898 editorial. He argued every black man lynched is a “big burly, black brute,” when in fact many were “attractive for white girls of culture and refinement to fall in love with them.” At the end of the editorial, Manly urged Felton to clean up her side of the argument first.

“Tell your men that it is no worse for a black man to be intimate with a white woman than for the white man to be intimate with a colored woman,” Manly wrote. “You set yourselves down as a lot of carping hypocrites, in fact you cry aloud for the virtue of your women while you seek to destroy the morality of ours. Don’t ever think that your women will remain pure while you are debauching ours. You sow the seed — the harvest will come in due time.”

The Democrats pounced on the editorial. It was so controversial, Republicans claimed the Democrats wrote it. Not Manly. But the damage was done.

White advertisers stopped doing business with The Daily Record. The owner of the newspaper’s Seventh Street office terminated Manly’s lease. He received death threats.

“They said Alex Manly had defamed white womanhood and the big black burly coon must not live,” Caroline Sadgwar Manly wrote in a 1953 letter.

Manly’s editorial is often cited as one of the instigators of the coup, but Zucchino said that in private, Waddell and the other leaders of the coup loved the editorial. It helped rally people to their cause. “The editorial gave them the pretext,” says Zucchino. “They were delighted. They were now justified in defending the honor of white women.”

Waddell, a former Confederate officer and U.S. congressman, was hired to lead the 1898 campaign. A good orator, he helped incite white citizens against the black community in Wilmington by vilifying Manly. “Few white men in Wilmington intended to back their candidates that November without the benefit of a firearm,” Zucchino writes in his book. “They had vowed to take charge of the city’s government by the ballot or the bullet, or both.”

Two months after the editorial was published, Waddell gave a speech at Thalian Hall, where he said allowing blacks to vote was “the greatest crime that has ever been perpetrated against modern civilization,” closing with what would later become the campaign’s rallying cry: “We will never surrender to a ragged raffle of Negroes, even if we have to choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses.”

The Coup

On Election Day, despite a heavy black turnout, Democrats won offices around the state. But Wilmington’s Fusionist government remained in power. Hugh MacRae — a Wilmington industrialist and one of the leaders of the coup — called for a meeting the next day. On Nov. 9, 1898, Wilmington Democrats gathered to hear Waddell read “The White Declaration of Independence.”

“We the undersigned citizens of the city of Wilmington and county of New Hanover, do hereby declare that we will no longer be ruled and will never again be ruled, by men of African origin,” the document stated. The declaration made several demands, including the banishment of several black leaders in the city, especially Alex Manly.

“A climax was reached when the Negro paper of this city published an article so vile and slanderous that it would in most communities have resulted in a lynching, and yet there is no punishment, provided by the courts, adequate for the offense,” the declaration said. “We, therefore, owe it to the people of this community and city, as protection against such license in the future, that ‘The Record’ cease to be published and that its editor be banished from this community,” the document said, adding “If the demand is agreed to, we counsel forbearance on the part of the white men. If the demand is refused or no answer is given within the time mentioned, then the editor, Manly, will be expelled by force.”

Waddell did not receive a response, so on the morning of Nov. 10, he led 500 white businessmen and veterans armed with rifles, and a Gatling gun, to the two-story publishing office of The Daily Record.

Manly was long gone and the building was empty. The mob broke down the door and smashed up the office, destroying Manly’s press. Kerosene from the office lamps was spread on the wood planks and set ablaze. Waddell’s men cheered as the building burned. Before they left, the mob posed for a photograph.

As the building burned, Waddell’s ranks swelled to about 2,000 men with shotguns and Winchester rifles. They marched from the paper toward Brooklyn, the majority-black neighborhood, destroying black businesses along the way.“One of the goals of the riots was to destroy the black middle class,” says Zucchino.

Rev. J. Allen Kirk, a pastor of Wilmington’s Central Baptist Church, hid in a graveyard as the mob attacked. “Firing began, and it seemed like a mighty battle in war time,” Kirk said in a statement. “The shrieks and screams of children, of mothers, of wives were heard, such as caused the blood of the most inhuman person to creep.”

While the white mob marched on Brooklyn, Waddell forced the Republican mayor, the police chief and board of aldermen to resign at gunpoint. A new government made up of Democrats was installed and Waddell was elected mayor. By the time he took office, between 60 and 300 black people were killed and about 20 were banished from the state.

Scars and Legacy

After passing through the guards, Manly went to North Carolina Congressman George White’s house in Washington. Caroline Sadgwar Manly was in London during the coup. She joined Manly in Washington and they were married in 1900.

The Manlys moved to Philadelphia. Manly never talked about what happened in Wilmington. “He was pretty shaken up,” says Zucchino. “He was surprised at the extent of the venom and viciousness that rose up.”

In letters to her sons, Caroline Sadgwar Manly says talking about what happened in 1898 “brings heartache.” “I like to write cheerful letters and there is too much sadness about that newspaper for me to tell you now, I will wait until I can find courage to tell you,” she writes in one letter to her sons. “I wish I could forget it.”

In another letter, she stops writing about what happened in Wilmington because her tears blot the ink.

When Waddell and his men burnt The Daily Record, it silenced the black press for a decade or more, according to a North Carolina commission report on the coup.

“Not until the development of the Cape Fear Journal in 1927 did the city have another regular African-American newspaper,” the report said.

Because of the coup, Manly’s legacy is incomplete, Gerard said.

“One of the costs of 1898, we don’t have a journalism professorship or journalism school named for Alex Manly. Instead, it was all nipped in the bud,” Gerard said.

Manly deserves recognition. He was not only the best kind of journalist — one that told the truth and held people accountable with facts — but he understood the power of a story and the responsibility the press has in telling it.

It’s no coincidence the mob marched from the armory on Market Street east to 7th Street to burn The Daily Record. Waddell and his co-conspirators made Alex Manly a public enemy, because when you deal in lies, the truth is the only threat. b

Kevin Maurer is an award-winning journalist and author who lives in Wilmington. His latest book is American Radical: Inside the World of an Undercover Muslim FBI Agent.