The 40-year journey to protect North Carolina’s ancient cypress forest

By Virginia Holman • Photographs By Dan Griffin & Charlie Peek

The Old Forest

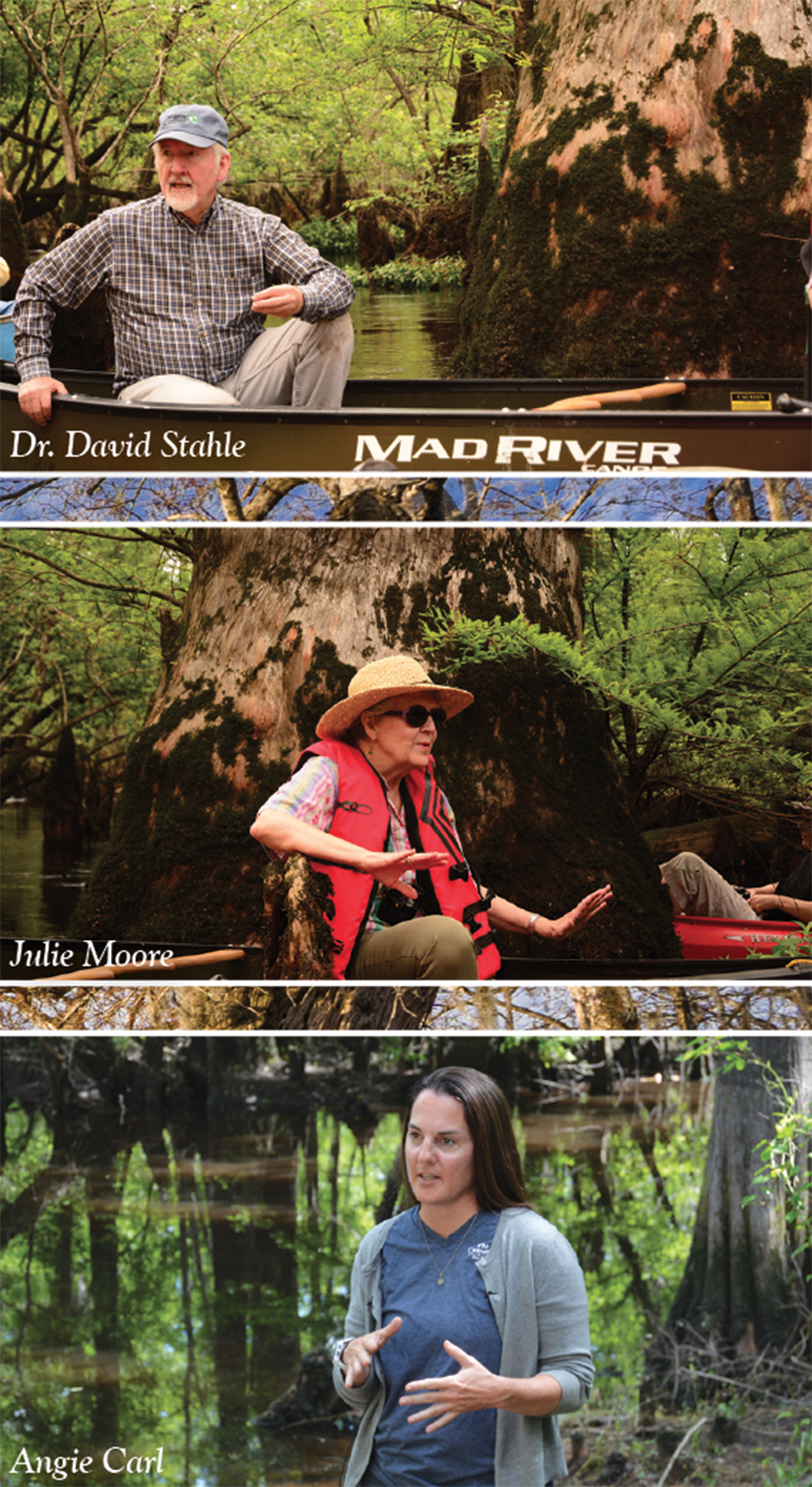

On May 9, 2019, in the rural floodplain hamlet of Ivanhoe, North Carolina, 12 members of the media gathered with conservationists at the bottom of a steep, soft sand driveway thick with coppery pine straw and spent catkins. There, beside the banks of a slow-moving blackwater swamp, esteemed dendrochronologist Dr. David Stahle, conservationist Julie Moore, and Angie Carl of the Nature Conservancy stood silent as a small congregation of writers and reporters prepared our recording devices and cameras.

Sunlight filtered through the brim of Julie Moore’s straw hat and spangled her cheeks. Dr. Stahle stood stalwart. He took a few deep breaths and swayed gently as he shifted his weight from foot to foot. Angie Carl caught his eye, and they exchanged a wistful glance, the kind that passes between in-laws at a wedding. She reached out and briefly rested a hand on his shoulder. We quieted soon after.

The purpose of this gathering was the formal announcement that we stood upriver of a 2,624-year-old living bald cypress tree, known in scientific circles as BLK227, now confirmed as the longest lived tree of its species known to exist and the fifth oldest known non-clonal tree species in the world.

It’s always thrilling when an ancient relic is found, both for the discoverers and for the public. Last year, news outlets reported an 8-year-old girl in Sweden pulled a rusted ribbon of metal from a lake bottom, raised it above her head like Excalibur and called to her father on shore. Her find? A pre-Viking sword that dates to the 5th century. A few months later, a Greek trading ship, dubbed the “Odysseus ship” because it is similar to the one depicted on the famous “Siren vase,” was found perfectly preserved, mast intact, 2,400 years after it sank to the anoxic bottom of the Black Sea. Such finds capture the minds of scientists and laypeople alike. They offer a keyhole glimpse of lost civilizations and lead us to wonder about those who created them.

Then there is a find like BLK227. This living tree is neither artifact nor relic, museum piece or monument. To think of a single tree as something separate from its forest risks false idolatry. Today, this almost incomprehensibly ancient bald cypress not only flourishes, it does so within a plant community full of ancient trees. These “multi-millennium old trees,” Stahle says, “stand cheek to jowl” throughout this wilderness. Heart rot has left many “so hollow, you can step inside, look straight up and see to heaven.” He estimates these elders at over 3,000 years. Within the context of so vast a measure of time, the works of humans may seem a folly, yet this old forest has endured the last few centuries both despite and because of us.

The River

The headwaters of the Black River rise with the confluence of the Great Coharie and Six Runs creeks. A long, mazy meander of a river, it slackens and constricts, pulses and flows the whole of its 66 miles. Below Ivanhoe, the Black absorbs its glade-like tributary, the South River. It surrenders its name and unites with the Cape Fear River 14 miles above Wilmington. According to historian Wilson Angley, in his Historical Overview of the Black River in Southeastern North Carolina: “In the early decades of the eighteenth century, the Black River was sometimes referred to as the Stumpy River, doubtless because of its numerous impediments to navigation.” A 1733 rendering of the “New and Correct” North Carolina map by Edward Moseley housed at East Carolina University lists this alternate name as the “Swampy River.” Both names are apt, for the areas where the cypress forest remains are both stumpy and swampy. There are other hazards as well. In places like the Three Sisters Swamp, thickets of cypress knees, partially submerged snags, sandbars, and interminable swaths of alligator weed can mean a long, hot, muddy portage during periods of low water. Venomous and nonvenomous snakes drop in the water from low-hanging branches and sometimes coil atop the cypress knees. The most insidious peril is one that befalls even the most seasoned local: they become utterly lost.

One somewhat mythic account, first published by renowned botanist Steven Leonard in the Fall 1985 North Carolina Wildflower Preservation Society Newsletter, recounts a story often told by Haws Bluff native Leon Horrell, a man who lived and worked much of his life near a Black River swamp. It’s described as a “secretive, mysterious, inaccessible place where the muck is too fluid to walk upon and too solid to boat through at low water, and when the river floods, the forest becomes myriad inter-connecting passage-ways.” Horrell spent a month each year on the Black River. From “Thanksgiving until Christmas Eve he pulls, poles, and paddles two tiny wooden boats into the labyrinth of sloughs and coves” to gather mistletoe. One day, Horrell sees an area of the swamp unfamiliar to him. He ties the towboat to a tree and enters. There he encounters “giant gnarled and buttressed cypress trees,” but when he tries to retrace his path back to the place he hitched the towboat full of mistletoe, he becomes disoriented. “He paddled methodically, carefully, searching for an elusive water path where everything would fit together as he pictured it in his mind. But nothing matched.” This “man of the swamp” manages to return home, but despite “countless trips,” his boat full of mistletoe is never found. Even today, large groups of paddlers routinely get separated and turned around in the swamps.

The Black River is a trickster; it winds through wilderness, and landmarks shift with the water level. A slough you paddle through one week may become a white sand island the next. Navigating these areas today is nearly impossible in anything other than a kayak or canoe, yet less than a century ago, the river was a bustling hub of commerce. Its heyday was between 1870 and 1924, a period when steamboats regularly made the trip between Wilmington and the small town of Clear Run. Steamers ferried barrels of tar, pitch, and turpentine — naval stores made from the extensive longleaf pine forests that once lay upland of the river–as well as loads of cypress. During this period, tugs, rafts, and shallow draft steamers needed unimpeded paths to ferry their cargoes. Dredging below the headwaters near Clear Run and extensive “river maintenance” was performed. Wilson Angley notes that in 1912 some “5,674 obstructions” were removed. Even so, he notes that boiler explosions, fires, and snags caused seven steamers and countless rafts to wreck on the river.

Why were ancient cypress trees like BLK227 spared the blade? There’s no single reason. Dr. Stahle says that the old trees likely were deemed “low-grade yellow cypress. Red cypress, on the other hand, was so desirable, you can barely find a stick of it now.” Also, the older a tree gets, the more “it gets shook,” as the saying goes. According to Hervey McIver of the Nature Conservancy, senescent cypress trees often “develop shakes or deep vertical splits along the grain.” When a tree like this is felled, McIver says, “the wood shatters,” rendering it useless for most commercial purposes. Finally, by the end of World War I, Wilson Angley notes that “steamboating in the lower Cape Fear region in general entered a rapid decline” due to the rise of reliable railways and roads and commercial destruction of the longleaf forest. The last steamboat on the Black was the Charles Whitlock, retired in 1926. Over the next 60 years, the naval stores industry faded, and the Black became known for its hunting and fishing.

The Trees

Julie Moore was the first person to direct Dr. Stahle to the ancient cypress swamp. “The first time I was on this river was in 1980. It was late one evening, and a forester who I knew [the late Dan Gilbert] contacted me because he wanted me to see an old forest that he was fascinated by — and considering that he cut down a lot of trees, it was interesting that he wanted me to see this site.” At the time, Moore worked for the state’s Natural Heritage Program, which cataloged important plant species across the state. She and Gilbert drove down as far as they could along the riverbank until Moore was able to see the edge of an ancient cypress forest. Then they got out and began walking. “We walked down as close to the river as we could to watch the wood ducks come in — they nested in the hollows of the cypress trees,” says Moore. “He didn’t say a word for about fifteen minutes; we just stood there. I’m getting goose bumps right now just thinking about it. It was one of those times that you know someone is sharing with you something that’s very important to him or her, and as it turns out, it’s a very important place.”

“We had already started having contract workers [including botanist Steven Leonard] survey Bladen and Pender counties for unusual natural areas . . . But nobody had ever been on the edges of the river, so we began exploring,” says Moore. Shortly after, Dr. Stahle wrote a letter to the Natural Heritage Program; he was looking for stands of old post oaks to study. Says Moore: “I picked up the phone, called him, and said, ‘We don’t have any of those post oaks you’re interested in, but we do have some old cypress.’”

In the mid-1980s, with Moore’s guidance, Stahle and a small team of scientists conducted extensive core sampling of several senescent cypress stands on the Black River. Moore says that ancient trees don’t always look like we expect: “Ancient trees aren’t always the tallest trees or the biggest trees.” They have what Dr. Stahle calls, “the gnarl factor.” Trees, like humans, grow gray and stooped, their limbs appear arthritic in very old age. So, Dr. Stahle and his team looked for trees with twisted, wrinkled gray trunks, heavy branches, small canopies and crowns that had the look of stag’s horns. In addition, these trees had to be solid enough to sample. Tree ring dating requires a continuous core sample from a solid area of tree trunk. Scientists use an auger and a tool called a Swedish increment borer. This hand-operated tool, which looks a bit like a giant corkscrew, is twisted at a precise angle with both hands from the exterior of the tree to its pith, gathering tree ring material into a long hollow tube that’s the width of a pencil. Coring can be precarious; scientists often balance on a tall ladder wedged in the muck in order to access solid areas high above the trees’ wide buttresses. Their research yielded exciting results. In 1987, Dr. Stahle was able to confirm existence of a tree nearly 1,700 years in age, BLK69, which soon became known locally as Methuselah.

The data obtained from core samples allows scientists to determine more than a tree’s age. Dr. Stahle and I first met two years ago, and he told me then that “tree rings are formed each growing season; they are annual, and they encode the imprint of regional climate on the width of the ring. So that means you can cross-synchronize growth patterns back in time among hundreds of trees, or even thousands, in a given climate province to determine what was happening climatologically in a given year.” Bald cypress, he said, are particularly sensitive and their rings provide exquisitely accurate historical information about periods of rain and drought. “The annual rain is a metric of tree growth for that year, and so the fat rings on bald cypress mean wet years and the skinny rings mean dry years. And the history of climate synchronizes growth in all the cypress trees in the Carolinas, they all show an annual rhythm of growth — good year, bad year — that cross-dates across the coastal plain. It is that imprint of climate variability that we in dendrochronology use to exactly synchronize the rings to the precise year in which they form.” That level of precision allowed for one startling discovery.

In 1998, in what he self-deprecatingly refers to as a “particularly slow news day,” The New York Times ran a front-page story about Stahle’s latest research, which concerned one of the oldest mysteries in Colonial America. Using data gathered from ancient cypress samples he’d taken in the 1980s in Virginia and North Carolina, he discovered that when Sir Walter Raleigh’s Roanoke colony was established — the Lost Colony — it coincided with an epic drought.

The New York Times wrote that Stahle’s research, which was published in the journal Science, “showed that the most extreme three-year growing-season drought in 800 years coincided exactly with the period in which the Roanoke colony was established and then vanished. The worst single season occurred in 1587, the year of Virginia Dare’s birth.” Though the particulars of the colonists’ fate will likely never be known, dendrochronology had shown that ancient bald cypress functioned as archivists, providing a detailed climate history, to quote poet Philip Larkin, “written down in rings of grain.”

The World

The Nature Conservancy’s Coastal Fire and Restoration Manager, Angie Carl, is concerned with the big picture — not only regarding the ancient trees but the health of their entire ecosystem. She first met Dr. Stahle in 2011, when he returned to Wilmington to give a talk and renew core-sampling the ancient cypress trees. Though she had managed the Black River Preserve since 2004, and knew the trees were ancient, it wasn’t until her second day in the field with Dr. Stahle, a day that she describes as the “best day of my career,” when she understood that this ancient forest was truly vast.

The first day, she, Dr. Stahle, graduate student Dan Griffin (now a professor at University of Minnesota) and experienced Black River guide Captain Charles Robbins ventured to area that contained numerous ancient trees, but it was the second day of the trip that both she and Dr. Stahle describe as astonishing. “We were near the area where BLK227 is located and we started exploring an area where he’d never been,” she says. “At one point, he got out of the johnboat and started wading through the forest. Dr. Stahle kept saying, ‘Angie! Angie! Angie! Count! Count! Count! 15, 18, 20!’ We’d get out every 10 minutes and walk, and there were hundreds, thousands, of ancient trees. He said, ‘Those are all millennial-age trees. I didn’t know it was this big.’”

Carl speaks of the ancient cypress trees in reverential tones, but she’s quick to deflect attention from herself — conservation is a team effort. She’s profoundly grateful to Dr. Stahle not only for his discoveries, but also for the renewed interest they’ve brought to preserving the area. She also credits Fred Annan and Hervey McIver with the Nature Conservancy, and Janice Allen with the Coastal Land Trust, all stalwart, experienced conservationists who have quilted together the extensive land acquisitions along the old forest. They’ve built meaningful relationships in the communities along the Black River, and have procured acreage and easements one hard-won parcel at a time. The result: The Nature Conservancy currently has 19,200 acres of land protected on the Black River, and the Coastal Land Trust has 2,000. Yet areas of the ancient cypress still remain on unprotected bottomland. Carl says the organization’s goal is to get the funds to purchase not only those unprotected ancient cypress stands but also to purchase and restore adjacent longleaf systems. “It’s not enough just to protect the ancient trees; to protect the forest, we need to protect the ecosystem. These areas are important to the health of the river, which is important to the health of the trees. We don’t manage areas for a single species; we manage for an intact functioning ecosystem.”

She points out that the Nature Conservancy appeals to people with diverse interests: “hunters, birdwatchers, people who fish, frog lovers, ancient tree lovers, people who care about air and water quality, people who care about bears, the prothonotary warblers or the red-cockaded woodpeckers. You might not like all of them, but odds are one of them is important to you.”

Cape Fear Riverkeeper Kemp Burdette echoes Carl’s call for a healthy river system: “Those swamps are a finely balanced ecosystem. Years ago, the Black River was considered one of the highest surface quality waterways in North Carolina.” Burdette says his testing of the water quality two years ago after significant rain events revealed consistently elevated levels of fecal coliform bacteria he says are from the large-scale hog and chicken farms upriver. Fecal waste is essentially fertilizer, and its effects can quickly alter the river environment. “It can cause algal blooms that reduce the oxygen in the water, cause fish kills, disrupt bird and animal habitats, and threaten the health of humans who come into contact with contaminated water,” says Burdette.

Conservation is a long game, a torch that’s passed from generation to generation. Efforts like those on the Black River, which began 40 years ago with the efforts of people like Julie Moore, have only grown in importance through time as new discoveries are made and newer threats revealed. “I’ve been in this business since I was 24 years old,” Moore told me a few days after our river trip, “and you have to be tough, because the conservation business is all about loss. For all the wonderful things that are happening right now on the Black River, there are hundreds of places that are gone — areas that I have personally known. That really does hurt, because we can’t get them back.”

When I asked her why the ancient trees are important, she fell quiet for a bit. “Have you ever heard the saying, ‘Trees hold the world together’? We have a moment to protect all of the ancient cypress on the Black River. People say things like, ‘Oh, you can just replant trees,’ but it’s impossible to replant an ancient forest. Once it’s gone, it’s pretty much gone . . . Those ancient trees have endured so much trauma. So many have lost their crowns. Now think about the ancient tree we saw that day in the swamp, it had that little green sprig right there at water level. It has enough energy and determination to keep living. That bit of new growth, that’s success.”

Author and creative writing instructor Virginia Holman lives and writes in Carolina Beach.